29 February 2012

I’m in Nature! Again‽

Back last October, I mentioned I was quoted briefly in Nature for an article on retractions.

Here it is, less than four months later, and I’m not only being quoted in Nature again, but more extensively. This time, it’s on matters arising from my Better Posters blog. I imagine there will be Nature readers will be thinking, “Him again?”

The article is available for free at the Nature Jobs website.

Reference

Powell K. 2012. Billboard science. Nature 483: 113-115. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nj7387-113a

Designing the Open Lab 2013 buttons

I’ve been pleased to have designed the submission buttons for the last three editions of The Open Laboratory anthology of online science writing (read Bora Zivcovic’s account here). That said, I was surprised when Bora emailed me asking for a new one, because a year ago, I wrote:

I hope that Bora and the Open Lab team will let me retire this design after Open Lab 2011 is published. I’d like to see something fresh for the Open Lab 2012 buttons, whether from me or someone else.

I wanted to do something completely different.

I had a concept in my head, but it was complicated. Without getting into the details (because I might still try it next year), I couldn’t pull it off. I procrastinated and felt guilty knowing that Bora was waiting.

Finally, a week or two ago, I was thinking how to convey the concept of something being “open.” I thought of an open window looking out to the sky

The design went quickly from there.

I grabbed a picture of a beautiful skyline. It had to have some clouds to be recognizable as sky, rather than a just blue. I enlarged the “O” to maximize the amount of sky visible though it.

Because the idea was to be looking through something onto the sky, I wanted the background to look like a wall. I went into Corel Photo-Paint and played around with textures. Bricks were too rigid and too structured and visually noisy, so I used a simple stone texture.

I wanted colours that would “pop” against the colours of the sky. I used the eyedropper tool to sample the RGB values of the sky blue, then used Kuler to find complementary colours. It suggested a lovely dark tan as the main contrast colour, so that became the colour of the “Open Lab” text.

The darker blue Kuler suggested as part of the colour scheme seemed right for the “Submit to” text. Enlarging the “O” created a space for the “Submit to” text, but because that space was smaller than previous years, the text needed to be more condensed. I opened up the drop down menu, and found MoolBoran almost immediately. I went back and tried other similar fonts, but nothing seemed to fit the bill as well.

Things were starting to shape up. The colour scheme had a light brown, so I decided to make the stone texture that colour. I wasn’t quite sure how to do that, because the texture had been created in black and white. I draw a box underneath the stone texture, filled it with the light tan colour, and looked for a tool to make the stone transparent.

The transparency tool I found did not do what I wanted. I wanted to make the stone background equally transparent, but this was a dynamic tool. As a result, I got a totally unplanned gradient, which added some nice shades that highlighted the “O.”

Remember, love your accidents.

Now I was roughly at this point:

I liked it, but there were still some issues, like the line spacing. The colour scheme? It was lovely and calming. It made me think of beautiful tropical beaches. But it was too subdued, particularly given that the last two years had gone for intense colour schemes (boiling lava two years ago and action movie orange and blue last year).

The last tweak was to bring a more visual interest by adding another typeface. Because the other typefaces were very geometric, I looked for something more relaxed and “swishy” to contrast to them. Scriptina was one of the first ones I tried. As with the “Submit” text, I went back and tried some other brush scripts, but none seemed to work as well as Scriptina. It fit the available space perfectly, and I loved how the “2” was almost hugging the “B.”

Though I say it myself, I think the result is rather lovely. It’s not as radically different as I originally planned, but it is different enough that it stands apart from the last three years.

And if you read something you like here or on any other science blog, don’t forget to click the button!

Related posts

Open Lab 2011 begins! Plus: About the buttons

Open Laboratory 2009 candidate logo design

28 February 2012

Not every radical idea is right

As it stands, our current system may work well in weeding out technically flawed proposals and advancing incremental work, yet truly novel ideas will rarely be funded or even tolerated.

This is not a particularly new insight. I’ve written about it from time to time; see here. I think we disagree on the value of incremental work, though. I think most scientific progress comes from incremental work, while Nicholson seems to think we get progress from “out of the box” thinking. Nicholson asks:

If, historically, most new ideas in science have been considered heretical by experts, does it make sense to rely upon experts to judge and fund new ideas?

It is true that some now accepted ideas in science were disputed at first, but Nicholson does not seem to consider that not every “novel idea” is ultimately vindicated. Case in point:

The emphasis on being liked by the scientific community as a prerequisite to survive as a practicing scientist subsequently limits critical exchange in science. This is the case with Peter Duesberg who went from a prestigious 7-year outstanding investigator grant from the NIH to grant-less ever since because he questioned the role of oncogenes in cancer and the role of HIV in AIDS.

You’re going to use HIV denial to build your case? Seriously? In a spectacular “own goal,” Nicholson inadvertently demonstrates exactly why funding agencies are conservative: because there are some people out there who have ideas that are just wrong. There are ideas that are not worth pursuing.

And I did a double take when I read this in the acknowledgements:

I thank Peter Duesberg (UC Berkeley) for useful comments and suggestions(.)

It might not be best form to use someone who gave you feedback on an article as an example of someone who’s been treated unfairly. This is in an article that complains about how “who you know” is contaminating science.

Nicholson says:

The novelty of an idea can be measured by how many ideas and people it contradicts.

Alas, the insanity of an idea can be measured in precisely the same way.

At the end of the article, Nicholson proposes a couple of ways out of dealing with fuddy-duddy old boys’s network of granting agencies. One is to incorporate more non-scientists into the review process. I might argue that we’ve seen some of the outcomes of non-scientists getting involved in the scientific process whenever we hear about politicians ragging on certain projects as “wasteful.”

Another solution, Nicholson argues, is crowdfunding. Having been involved in a crowdfunding project (SciFund), I’ve heard concerns that cranks will use crowdfunding to get money for their goofy projects. I think that crowdfunded research projects should have some form of peer review to keep out the crazies.

Reference

Nicholson J. 2012. Collegiality and careerism trump critical questions and bold new ideas: A student's perspective and solution. BioEssays: in press. DOI: 10.1002/bies.201200001

Tuesday Crustie: I bless the rains down in Africa

A lovely picture of a freshwater crab in the family Potamonautidae from West Africa.

Photo by brian.gratwicke on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

27 February 2012

A day in the field

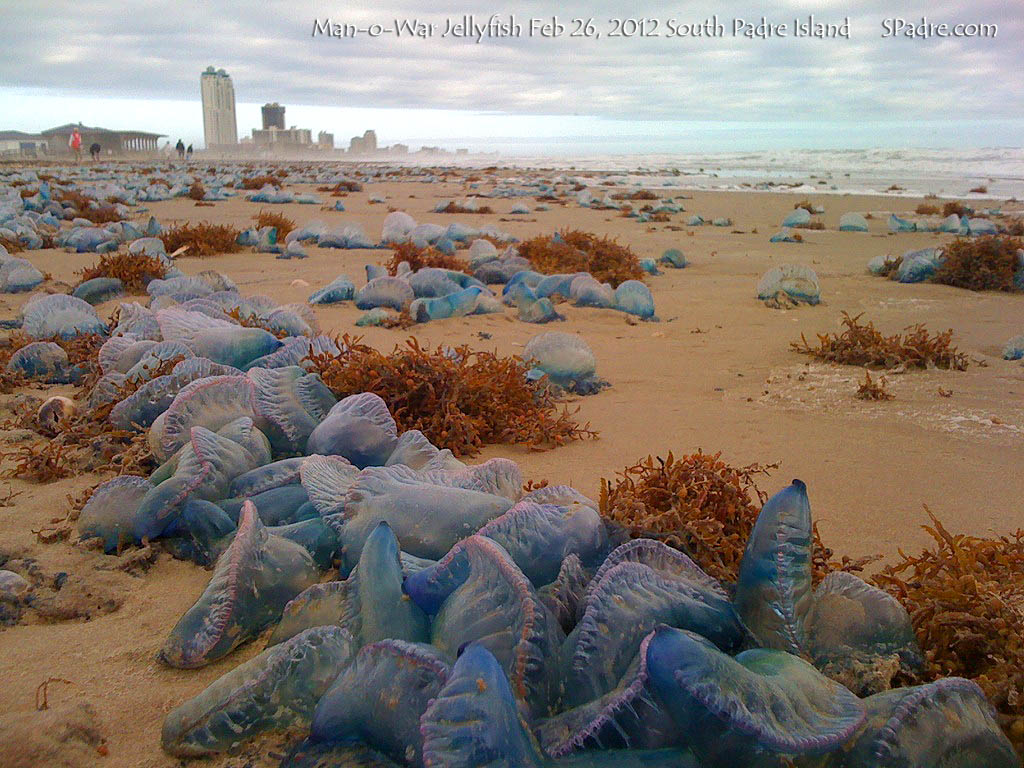

I have a project that is requiring monthly collection at the beach on South Padre Island. The weather hasn’t been great, or I’ve had other tasks to do, most of February. This meant I almost had to go out and collect this weekend.

I was surprised when I got there, because “blue” is not a colour I normally see a lot of on our beach.

And going closer, I realized...

That this was a veritable invasion of Portuguese men of war.

Despite my best efforts to avoid them, one caught in a retreating wave got its tentacles on my shins. And I can now say with certainty that this is not an experience I recommend. I would call it a stinging, burning sort of sensation. Rather like a localized sunburn.

Fortunately, the water was chilly, so the coolness of the water numbed the sensation. Somewhat.

I also learned that the covers of Rite in the Rain all weather notebooks are almost exactly the same colour as the sand on South Padre Island, which means if, say, a notebook were to fall down to the sand on the beach, it can be rather difficult to see.

Furthermore, while Rite in the Rain products – such as their No. 37 pen – are indeed waterproof, they aren’t sand proof. And I discovered sand can get into all sorts of places that can gum up the works of a pen.

The things one does for data.

Excuse me... datum. “Data” is plural, so we would need to have found more than one animal to have data.

Last pic from here.

I was surprised when I got there, because “blue” is not a colour I normally see a lot of on our beach.

And going closer, I realized...

That this was a veritable invasion of Portuguese men of war.

Despite my best efforts to avoid them, one caught in a retreating wave got its tentacles on my shins. And I can now say with certainty that this is not an experience I recommend. I would call it a stinging, burning sort of sensation. Rather like a localized sunburn.

Fortunately, the water was chilly, so the coolness of the water numbed the sensation. Somewhat.

I also learned that the covers of Rite in the Rain all weather notebooks are almost exactly the same colour as the sand on South Padre Island, which means if, say, a notebook were to fall down to the sand on the beach, it can be rather difficult to see.

Furthermore, while Rite in the Rain products – such as their No. 37 pen – are indeed waterproof, they aren’t sand proof. And I discovered sand can get into all sorts of places that can gum up the works of a pen.

The things one does for data.

Excuse me... datum. “Data” is plural, so we would need to have found more than one animal to have data.

Last pic from here.

24 February 2012

Models

“We did this experiment with a mouse model.”

What, like this?

Why not just say “mice” instead of “mouse model”?

If you want to say “mouse model,” make sure that you are clear what the mice are models of. Models are stand ins or representations for something else. In biomedical research, mice are models for human diseases. Saying, “We used a mouse model of human schizophrenia” or “mouse model of human obesity” is fine.

But for something like the genetics of fur colour on mate selection probably means the mouse are not a model for anything else, it’s just a straight up inquiry into mouse biology. Mice for mice’s sake.

What, like this?

Why not just say “mice” instead of “mouse model”?

If you want to say “mouse model,” make sure that you are clear what the mice are models of. Models are stand ins or representations for something else. In biomedical research, mice are models for human diseases. Saying, “We used a mouse model of human schizophrenia” or “mouse model of human obesity” is fine.

But for something like the genetics of fur colour on mate selection probably means the mouse are not a model for anything else, it’s just a straight up inquiry into mouse biology. Mice for mice’s sake.

23 February 2012

Walk up to that bear

“See that bear?”

“That one there? Yeah.”

“Go walk up to it.”

“What?”

“Go on. Just walk up to it.”

“Um...”

That’s the sort of dialogue I heard in my head with I read the title, “Behaviour of solitary adult Scandinavian brown bears (Ursus arctos) when approached by humans on foot.”

That’s the sort of dialogue I heard in my head with I read the title, “Behaviour of solitary adult Scandinavian brown bears (Ursus arctos) when approached by humans on foot.”

Large mammals and humans often don’t get along well, and this is true of bears, too. Bears are a threat to humans, and humans are a threat to bears. This particular bear species is not doing so well in the wild, with several countries having a few hundred to a few thousands.

The researchers located 30 bears that had been given radio collars. That way, the positions of the bears were known to the people walking towards them. Many, if not all of the bears, were approached multiple times, but those were at least two weeks apart. One to four people started almost a kilometer away from the bear. The observers’ path was always upwind of the bear, so the bear would have scent cues coming from the people and would be less likely to be surprised.

As part of the objective was to simulate hikers, the observers were keep a normal hiking pace and talk to each other. The authors noted, though:

I imagine some poor bear sitting in the forest thinking, “Hoooooo boy. That one’s crazy.”

Most of the time, even knowing where the bears were, people only managed to see them about 15% of the time. Typically (80% of the time), the bears walked away from where they had been. None of the bears ever showed any signs of aggression towards people.

It’s good news that humans have little to fear from these bears. I do worry, though, that the bears might have a bit more to worry about from humans. I used to work in Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta (one of my favourite places on the planet, by the way), and hikers were always being warned about bears. The black bears and grizzlies in the region, while not aggressive, are not exactly retiring, either. And humans in those parks have gotten themselves into all sorts of trouble by doing stupid things around bears. I do worry that if people think that Scandinavian bears are mostly harmless, people might do incredibly stupid things around the bears (trying to get a picture, and so on.)

Reference

Moen G, Støen O, Sahlén V, Swenson J. 2012. Behaviour of solitary adult Scandinavian brown bears (Ursus arctos) when approached by humans on foot PLoS ONE 7(2): e31699. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031699

Picture by ucumari on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

“That one there? Yeah.”

“Go walk up to it.”

“What?”

“Go on. Just walk up to it.”

“Um...”

Large mammals and humans often don’t get along well, and this is true of bears, too. Bears are a threat to humans, and humans are a threat to bears. This particular bear species is not doing so well in the wild, with several countries having a few hundred to a few thousands.

The researchers located 30 bears that had been given radio collars. That way, the positions of the bears were known to the people walking towards them. Many, if not all of the bears, were approached multiple times, but those were at least two weeks apart. One to four people started almost a kilometer away from the bear. The observers’ path was always upwind of the bear, so the bear would have scent cues coming from the people and would be less likely to be surprised.

As part of the objective was to simulate hikers, the observers were keep a normal hiking pace and talk to each other. The authors noted, though:

When just one observer approached the bear, this person talked to him- or herself.

I imagine some poor bear sitting in the forest thinking, “Hoooooo boy. That one’s crazy.”

Most of the time, even knowing where the bears were, people only managed to see them about 15% of the time. Typically (80% of the time), the bears walked away from where they had been. None of the bears ever showed any signs of aggression towards people.

It’s good news that humans have little to fear from these bears. I do worry, though, that the bears might have a bit more to worry about from humans. I used to work in Waterton Lakes National Park in Alberta (one of my favourite places on the planet, by the way), and hikers were always being warned about bears. The black bears and grizzlies in the region, while not aggressive, are not exactly retiring, either. And humans in those parks have gotten themselves into all sorts of trouble by doing stupid things around bears. I do worry that if people think that Scandinavian bears are mostly harmless, people might do incredibly stupid things around the bears (trying to get a picture, and so on.)

Reference

Moen G, Støen O, Sahlén V, Swenson J. 2012. Behaviour of solitary adult Scandinavian brown bears (Ursus arctos) when approached by humans on foot PLoS ONE 7(2): e31699. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031699

Picture by ucumari on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

22 February 2012

Helping the most people

“I want to help people.”

Many pre-med students usually say or write some variation of that when asked why they want to go to medical school. Indeed, the most popular university major across the United States, I am told, is pre-med biology.

For those of you American pre-meds, if you want to help people, go into health and insurance policy.

I'm a reasonably healthy guy (I’ve never cancelled a class due to illness). I’ve got full-time employment that is more stable than most jobs. And the thought of an extended encounter with the American medical system scares the hell out of me. I am constantly aware of how charges start to rack up, even if insurance is picking up most of the tab. And there’s always the prospect that insurance won’t pick up the tab.

We have plenty of prospective physicians and health care providers. Real help will come from changing policies so more people can get to the health care providers.

Related links

Trying to catch his breath with a hole-ridden safety net

Many pre-med students usually say or write some variation of that when asked why they want to go to medical school. Indeed, the most popular university major across the United States, I am told, is pre-med biology.

For those of you American pre-meds, if you want to help people, go into health and insurance policy.

I'm a reasonably healthy guy (I’ve never cancelled a class due to illness). I’ve got full-time employment that is more stable than most jobs. And the thought of an extended encounter with the American medical system scares the hell out of me. I am constantly aware of how charges start to rack up, even if insurance is picking up most of the tab. And there’s always the prospect that insurance won’t pick up the tab.

We have plenty of prospective physicians and health care providers. Real help will come from changing policies so more people can get to the health care providers.

Related links

Trying to catch his breath with a hole-ridden safety net

21 February 2012

Tuesday Crustie: Smooth

20 February 2012

The Zen of Presentations, Part 50: “I hate this topic”

It’s easy to give a talk about your own research. Your own story. Your own project.

What about those times when you have to give a presentation on a topic that... frankly... doesn’t wind your crank? As an instructor, I often have to give presentations on topics that I don’t care about. When I first started here, I had to teach general biology, which included a bunch of material that, to be honest, I had never learned before. The old joke is that in your first semester teaching a class, all you have to be is one lesson ahead of the students.

The path of least resistance is to aim for factual competence. If you’re coming into a subject cold, your first concern is to say things that are correct so you won’t look like an idiot. But “just the facts” doesn’t makes for a compelling presentation. Anyone who wants facts can Google answers faster than you can present them.

Sometimes, people presenting on something they didn’t choose will undercut their own material. They’ll indicate, sometimes explicitly, sometimes through hints, that they don’t like the topic.

Having disdain for your subject is lethal to a presentation. If you signal that this is not important to you, you are signalling that it’s not important to the audience. Which makes it a great big waste of time for all concerned.

Not everyone has the same interests, though. Some people may get something out of it that you don’t. If you respect your audience, at least pretend to have a good time while you’re up there!

But it’s even better if you can go a step beyond getting the facts right and putting on the fake service industry smile.

I once heard an interview with an educator who talked about this problem. He argued that an instructor had to find some sort of personal connection with the material.

The question came up: How do you find a personal connection with, say, the Pythagorean theorem? Trigonometry can be an abstract, bloodless subject.

His answer was to talk about how the ancients calculated the size of the earth. In the city of Syrene, there was a well that the sun shone down directly at noon on a particular day of the year. On the same day in the city of Alexandria, the sun didn’t shine directly overhead. A post would cast a short shadow.

From those two pieces of information, the mathematician Eratosthenes calculated the size of the Earth...

...And came very close to the right answer.

The person being interviewed found this fascinating, and that was his personal connection to this particular bit of geometry. And you can see why: it’s a great story.

“And if you don’t find that personal connection?” asked the interviewer.

“Boredom. Endless boredom.”

I faced a similar problem teaching aerobic respiration, which is soul destroying in the wrong hands. I needed a hook that made presenting it interesting to me. What I eventually hit on was to use a block of chocolate, with six pieces. I tell the students each piece of chocolate represents one carbon atom in a glucose molecule. As we go through the process of turning a sugar molecule into ATP, I break the chocolate down and give each piece (representing carbon in the exhaled carbon dioxide) to a student.

To be honest, I don’t know if having the chocolate model helps the students learn at all. But that wasn’t the point: I do it for me. Because I needed a way to engage with cellular respiration and have fun with it. Because if I’m not engaged, why should I be surprised if my students are not engaged?

There should always be a way to connect with the material. An eloquent person should find no subject sterile.

What about those times when you have to give a presentation on a topic that... frankly... doesn’t wind your crank? As an instructor, I often have to give presentations on topics that I don’t care about. When I first started here, I had to teach general biology, which included a bunch of material that, to be honest, I had never learned before. The old joke is that in your first semester teaching a class, all you have to be is one lesson ahead of the students.

The path of least resistance is to aim for factual competence. If you’re coming into a subject cold, your first concern is to say things that are correct so you won’t look like an idiot. But “just the facts” doesn’t makes for a compelling presentation. Anyone who wants facts can Google answers faster than you can present them.

Sometimes, people presenting on something they didn’t choose will undercut their own material. They’ll indicate, sometimes explicitly, sometimes through hints, that they don’t like the topic.

Having disdain for your subject is lethal to a presentation. If you signal that this is not important to you, you are signalling that it’s not important to the audience. Which makes it a great big waste of time for all concerned.

Not everyone has the same interests, though. Some people may get something out of it that you don’t. If you respect your audience, at least pretend to have a good time while you’re up there!

But it’s even better if you can go a step beyond getting the facts right and putting on the fake service industry smile.

I once heard an interview with an educator who talked about this problem. He argued that an instructor had to find some sort of personal connection with the material.

The question came up: How do you find a personal connection with, say, the Pythagorean theorem? Trigonometry can be an abstract, bloodless subject.

His answer was to talk about how the ancients calculated the size of the earth. In the city of Syrene, there was a well that the sun shone down directly at noon on a particular day of the year. On the same day in the city of Alexandria, the sun didn’t shine directly overhead. A post would cast a short shadow.

From those two pieces of information, the mathematician Eratosthenes calculated the size of the Earth...

...And came very close to the right answer.

The person being interviewed found this fascinating, and that was his personal connection to this particular bit of geometry. And you can see why: it’s a great story.

“And if you don’t find that personal connection?” asked the interviewer.

“Boredom. Endless boredom.”

I faced a similar problem teaching aerobic respiration, which is soul destroying in the wrong hands. I needed a hook that made presenting it interesting to me. What I eventually hit on was to use a block of chocolate, with six pieces. I tell the students each piece of chocolate represents one carbon atom in a glucose molecule. As we go through the process of turning a sugar molecule into ATP, I break the chocolate down and give each piece (representing carbon in the exhaled carbon dioxide) to a student.

To be honest, I don’t know if having the chocolate model helps the students learn at all. But that wasn’t the point: I do it for me. Because I needed a way to engage with cellular respiration and have fun with it. Because if I’m not engaged, why should I be surprised if my students are not engaged?

There should always be a way to connect with the material. An eloquent person should find no subject sterile.

17 February 2012

Upcoming San Antonio talk in neurobiology

I’m on the road today, in San Antonio for a big grant planning meeting. Just a quick smash and grab, barely time to do anything. But that I’m here reminds me...

I’ll be back.

Specially, I’ll be at the University of Texas San Antonio Neuroscience Institute, speaking as part of their spring seminar series on Thursday, 8 March 2012 at 12:30 pm, in room AET 0.102. And if you haven’t been on campus before, here’s a map.

The talk is titled, “Are the spineless painless?” It’s about invertebrate nociception.

I’ll be back.

Specially, I’ll be at the University of Texas San Antonio Neuroscience Institute, speaking as part of their spring seminar series on Thursday, 8 March 2012 at 12:30 pm, in room AET 0.102. And if you haven’t been on campus before, here’s a map.

The talk is titled, “Are the spineless painless?” It’s about invertebrate nociception.

16 February 2012

Incentives to do this job

An article on the Austin American-Statesman discusses a proposal to change post-tenure review in the University of Texas system. Texas has had post-tenure review for a long time.

The details don’t interest me so much as some of the rationale for post-tenure review (my emphasis):

I have incentives to do my job.

Incentives like pride.

Curiosity. Desire to help students. I have plenty of incentives to do my job. It’s just that a lot of them are internal. They matter to me, not just because of the dollar value. If I was only interested in external incentives (i.e., money), I would have pursued a different career.

I don’t buy Lindsay’s implication that the only reason anyone does anything, ever, is because there is some external carrot or stick.

The details don’t interest me so much as some of the rationale for post-tenure review (my emphasis):

“It increases the accountability universities have to demonstrate to taxpayers that their money's being spent productively,” said Thomas Lindsay, director of the (Texas Public Policy Foundation)’s Center for Higher Education. “I think it's pretty unobjectionable... unless we believe faculty are alone among human beings in requiring no incentives to do their job.”

I have incentives to do my job.

Incentives like pride.

Curiosity. Desire to help students. I have plenty of incentives to do my job. It’s just that a lot of them are internal. They matter to me, not just because of the dollar value. If I was only interested in external incentives (i.e., money), I would have pursued a different career.

I don’t buy Lindsay’s implication that the only reason anyone does anything, ever, is because there is some external carrot or stick.

15 February 2012

Miniature chameleons: beyond the “Squee!”

You went, “Squee!”, didn’t you?

This is Brookesia micra, the smallest of the new species. There are four species described in this paper, shown below:

From top to bottom, they are Brookesia tristis, Brookesia confidens, Brookesia micra (which you saw above), and Brookesia desperata.

But as I was browsing through the paper, I hit this. And it stopped me cold.

It’s the description of the name of one of the species, Brookesia tristis.

Etymology.— The species epithet is an adjective derived from the Latin “tristis” meaning “doleful”, “sad”, “sorrowful”, and refers to the fact that the entire known range of this species (Montagne des Français) suffers from severe deforestation and habitat destruction despite recently being declared as a nature reserve.

I just found this so sad. The authors are so pessimistic about the chances for the survival of this marvelous little species, they have made the gloomy survival prospects of the formal scientific name of the species.

Another species, Brookesia desperata, has a similar section describing the rationale for its name:

Etymology.— The species epithet is an adjective derived from the Latin “desperatus” meaning “desperate”. Although the known range of the species is within a nature reserve established decades ago, its habitat is in truth barely protected and subject to numerous human-induced environmental problems resulting in severe habitat destruction [41], thus threatening the survival of the species.

I am glad that one species gets a more optimistic name:

Etymology.— The species epithet is an adjective derived from the Latin “confidens” meaning “confident”, “trusting”. The known range of the species is supposedly a well protected nature reserve with apparently limited habitat destruction. Furthermore, this area might benefit from natural protection by the tsingy limestone formations which are difficult to access, thus giving hope for the species’ survival.

A lot of the news coverage is focusing on the tiny size and the cuteness of these animals (io9, Gizmodo, Gizmodo Australia, MSNBC, Our Amazing Planet). Only one of the stories I have seen so far have mentioned the extreme pessimisn about the species’ continued survival. And – surprise! it’s The Daily Mail, which I mocked a while back for their headline hogwash. Their story says:

The new additions to the chameleon species are only found in an area just a few square miles in size.

Experts believe they may be especially sensitive to habitat destruction.

A big part of the discussion section of this paper is about “microendemism” This is the fancy way of saying that these chameleon species, and their relatives in this genus, all appear to have very small, restricted ranges. Presumably, they are just not able to disperse from location to location, so even minor geographic barriers becomes insurmountable to these creatures.

I’m actually terribly worried now that someone will look at these, see only the cuteness, and try to go collect them for the pet trade. That could be devastating to this species.

I wish more articles that tell people about these marvelous little animals would use the opportunity to tell people that if we’re not careful, we could lose them before we even get to know them.

Reference

Glaw F, Köhler J, Townsend T, & Vences M (2012). Rivaling the world's smallest reptiles: discovery of miniaturized and microendemic new species of leaf chameleons (Brookesia) from Northern Madagascar PLoS ONE, 7 (2) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031314

Additional: The United Academics blog, seemingly working from press releases, does mention the conservation angle. This makes me suspect that the conservation aspect of the story is there is the press release, but it being overlooked to sell the cute. The BBC and New Scientist, to their credit, also mention the tiny ranges as a problem for these species. Wired mentions the small ranges but not the conservation issue.

More additional: Hm. The Daily Mail got the conservation right, but may have broken an embargo to do it.

Even more additional: Some discussion about whether captive breeding could be a good thing for these species on Google+.

Comments for first half of February, 2012

The SeaMonster blog points out that it’s hard to discuss issues when there are people lying loudly and repeatedly. That doesn’t absolve you of responsibility to be a better communicator.

The Scholarly Kitchen doesn’t understand why people are boycotting Elsevier.

Janet Stemwedel looks at the predictive power of GRE scores.

Bradley Voytek justifies basic research, as it is often justified, by saying it’s practical.

Drugmonkey looks at the Elsevier boycott and obstacles to it getting traction in the medical research community.

Jerry Coyne asks how many have read Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. I have. If you want a short version of the book in Darwin’s own words, look at the Introduction to The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication.

The cool profs are wearing teal berets, according to Namnezia.

The Scholarly Kitchen doesn’t understand why people are boycotting Elsevier.

Janet Stemwedel looks at the predictive power of GRE scores.

Bradley Voytek justifies basic research, as it is often justified, by saying it’s practical.

Drugmonkey looks at the Elsevier boycott and obstacles to it getting traction in the medical research community.

Jerry Coyne asks how many have read Darwin’s On the Origin of Species. I have. If you want a short version of the book in Darwin’s own words, look at the Introduction to The Variation of Animals and Plants under Domestication.

The cool profs are wearing teal berets, according to Namnezia.

14 February 2012

Tuesday Crustie: What’s on the tube tonight, then?

I love the pose on this little crayfish (reported as Cambarellus patzcuarensis). Almost tempting to have a caption contest for this one...

Photo by susanne.lajcsak on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

13 February 2012

Order of magnitude

In October 2009, I was celebrating that this blog had received 10,000 views on the Research Blogging website.

I’m disappointed that I missed the odometer turning over:

But glad that it did turn over. Thank you!

I’m disappointed that I missed the odometer turning over:

But glad that it did turn over. Thank you!

How Pompeii worms take the heat

This is the Pompeii worm (Alvinella pompejana), and it is a record-holding animal.

Its record is not for the most unlikely animal (though you have to admit, it is a bit odd looking). You are looking at the animal that is able to withstand higher temperatures than anything else in the animal kingdom. The Pompeii worm routinely withstands scalding 80°C water. Not only that, it can routinely go outside of that to water that is more like room temperature, at 20°C.

Its record is not for the most unlikely animal (though you have to admit, it is a bit odd looking). You are looking at the animal that is able to withstand higher temperatures than anything else in the animal kingdom. The Pompeii worm routinely withstands scalding 80°C water. Not only that, it can routinely go outside of that to water that is more like room temperature, at 20°C.

That this worm is able to take high temperatures makes sense when you consider where these animals live. These are one of the deep sea vent animals that live near water hot enough to melt lead. As I described recently, the animals themselves don’t venture into the superheated water, but stray close enough that temperature is a consideration for them. And when they move away from the water erupting from the bottom of the ocean floor, they can face temperatures that are only a few degrees above freezing.

Most organisms cannot go into temperatures that high, because their proteins, including all the vital enzymes that catalyze almost every reaction in every cell, should be coming apart at the seams. Proteins are long, strand-like molecules, and they work because that strand is folded into complicated shapes. Those shapes are held together by a whole bunch of complex chemical bonds. But high temperatures can break chemical bonds. You see this process in action every time you cook an egg: the high temperatures break the chemical bonds holding the proteins in their particular shapes, and you get new shapes with different properties. This is why eggs go from runny and clear to more solid and white.

A new paper, authored by Jollivet and team, tries to work out just how the proteins in the Pompeii worm are able to hold together in conditions that would turn ours all sproggly (that's the technical term). They do this by a lot of molecular biology to look at the structure of the proteins in the worms en masse. They note two things.

First, the proteins in the Pompeii worm do not like to dissolve in water (hydrophobic). I don’t pretend to exactly understand how that stabilizes the protein, but it seems to be a trend that is also seen in bacteria that thrive in hot springs and the like.

Second, the proteins in the Pompeii worm have a lot of ionized bits. This made a little more intuitive sense to me, as I could imagine how having lots of positive and negative charges in the proteins would allow for the formation of more ionic bonds (salt bridges) along the length of the protein. More bonds within the protein should mean more stability. Ionic bonds are reasonably strong (weaker than covalent bonds, stronger than hydrogen bonds and Van der Waals forces).

The authors take this analysis one step further, and look not only at the Pompeii worm, but a relative (Paralvinella grasslei; alas, it seems to have no common English name), which is nowhere near as tolerant of those high temperatures. Jollivert and company found that many of the changes they saw were not unique to the Pompeii worm; P. grasslei showed some of the same trends. Both worms seemed to have a trend to hydrophobic proteins compared to other species. The authors suggest that the common ancestor of the two may have been more like the Pompeii worm in liking hot water, and that Paralvinella grasslei migrated back into cooler waters during its evolution.

Hot worm. Cool science.

Reference

Jollivet D, Mary J, Gagnière N, Tanguy A, Fontanillas E, Boutet I, Hourdez S, Segurens B, Weissenbach J, Poch O, Lecompte O. 2012. Proteome adaptation to high temperatures in the ectothermic hydrothermal vent Pompeii worm. PLoS ONE 7(2): e31150. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031150

That this worm is able to take high temperatures makes sense when you consider where these animals live. These are one of the deep sea vent animals that live near water hot enough to melt lead. As I described recently, the animals themselves don’t venture into the superheated water, but stray close enough that temperature is a consideration for them. And when they move away from the water erupting from the bottom of the ocean floor, they can face temperatures that are only a few degrees above freezing.

Most organisms cannot go into temperatures that high, because their proteins, including all the vital enzymes that catalyze almost every reaction in every cell, should be coming apart at the seams. Proteins are long, strand-like molecules, and they work because that strand is folded into complicated shapes. Those shapes are held together by a whole bunch of complex chemical bonds. But high temperatures can break chemical bonds. You see this process in action every time you cook an egg: the high temperatures break the chemical bonds holding the proteins in their particular shapes, and you get new shapes with different properties. This is why eggs go from runny and clear to more solid and white.

A new paper, authored by Jollivet and team, tries to work out just how the proteins in the Pompeii worm are able to hold together in conditions that would turn ours all sproggly (that's the technical term). They do this by a lot of molecular biology to look at the structure of the proteins in the worms en masse. They note two things.

First, the proteins in the Pompeii worm do not like to dissolve in water (hydrophobic). I don’t pretend to exactly understand how that stabilizes the protein, but it seems to be a trend that is also seen in bacteria that thrive in hot springs and the like.

Second, the proteins in the Pompeii worm have a lot of ionized bits. This made a little more intuitive sense to me, as I could imagine how having lots of positive and negative charges in the proteins would allow for the formation of more ionic bonds (salt bridges) along the length of the protein. More bonds within the protein should mean more stability. Ionic bonds are reasonably strong (weaker than covalent bonds, stronger than hydrogen bonds and Van der Waals forces).

The authors take this analysis one step further, and look not only at the Pompeii worm, but a relative (Paralvinella grasslei; alas, it seems to have no common English name), which is nowhere near as tolerant of those high temperatures. Jollivert and company found that many of the changes they saw were not unique to the Pompeii worm; P. grasslei showed some of the same trends. Both worms seemed to have a trend to hydrophobic proteins compared to other species. The authors suggest that the common ancestor of the two may have been more like the Pompeii worm in liking hot water, and that Paralvinella grasslei migrated back into cooler waters during its evolution.

Hot worm. Cool science.

Reference

Jollivet D, Mary J, Gagnière N, Tanguy A, Fontanillas E, Boutet I, Hourdez S, Segurens B, Weissenbach J, Poch O, Lecompte O. 2012. Proteome adaptation to high temperatures in the ectothermic hydrothermal vent Pompeii worm. PLoS ONE 7(2): e31150. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031150

09 February 2012

When scientists’ and publishers’ motivations align

Continuing with the theme of the similarity between game publishing and academic publishing, I learned this morning that a game publisher had crowdfunded over $400,000 in less than 24 hours. As I look now, it’s passed half a million bucks. With 33 days to go.

As someone who worked his butt off for a month to hit a grand through crowdfunding, I am in awe.

This analysis is good. (Here’s another.) It takes apart the question if creatives need middlemen like publishers any more. But this bit made me stop and think about scientific publishing:

This is one reason why I don’t know if the calls to boycott Elsevier (say) can be sustained. There are a lot of scientists who are trying to get famous. (Probably not so many trying to get rich.)

For example, consider the discussions about the perceived need to publish in certain journals (here and here). I want to excerpt Björn Brembs’s description of his situation:

For many scientists, their goals remain aligned with the goals of academic publishers. Clearly some of that desire for “fame” is not actually a desire to be in the public eye, but scientific fame enough to yield job security. How do we break this? Attitudes of hiring committees would have to change, dramatically and explicitly. Even then, there might be enough scientists who want fame or wealth to keep the for profit academic publishers in the game for a while yet.

As someone who worked his butt off for a month to hit a grand through crowdfunding, I am in awe.

This analysis is good. (Here’s another.) It takes apart the question if creatives need middlemen like publishers any more. But this bit made me stop and think about scientific publishing:

Are you trying to get famous or rich?

If the answer to either of these questions is yes, then it’s my opinion that you’ll still need a publisher. Why? Because your motivations are clearly aligned.

This is one reason why I don’t know if the calls to boycott Elsevier (say) can be sustained. There are a lot of scientists who are trying to get famous. (Probably not so many trying to get rich.)

For example, consider the discussions about the perceived need to publish in certain journals (here and here). I want to excerpt Björn Brembs’s description of his situation:

If you don't get any CNS papers in this field, you face only few job options, none of which mean that you’ll be able to spend much time on doing the research as you’re used to: 1) a teaching position at a small liberal arts college (and good luck with that with most of your time spent on research, but not getting a CNS) 2) salesman for the pharma industry 3) pipetteer for hire 4) flipping burgers. Which simply means that if you can't fathom doing anything else but science, you better get published in CNS.

Just take my example, which, from my experience and some statistics, is quite representative: In the last 6/7 years I have applied to about 120 tenure-track positions world-wide (i.e., North America, Japan, Australia, Europe), most applications went out before 2008, everything from small liberal arts to research one - basically I applied to anything that had ‘neuro’ somewhere in the description. Until then I had 1 Science paper, and 2-3 papers in the 7-10 IF range, approx. an average of about 1.2-1.4 papers per year, productivity wise. In total, I received less than 10 interview invitations and with very few exceptions, the other invited candidates had also all published in CNS (Cell, Nature, or Science - ZF). Informally, I was told that some positions I wasn’t invited for interview, this happened because I had to few hi-rank papers. With 60-600 applicants per tenure-track position, virtually everybody simply makes a cut at 1 CNS paper or so and then looks at the remaining candidates for a fit.

For many scientists, their goals remain aligned with the goals of academic publishers. Clearly some of that desire for “fame” is not actually a desire to be in the public eye, but scientific fame enough to yield job security. How do we break this? Attitudes of hiring committees would have to change, dramatically and explicitly. Even then, there might be enough scientists who want fame or wealth to keep the for profit academic publishers in the game for a while yet.

Pitfalls to grad school

At a recent info session on graduate programs, prospective grad students asked me about the degree plan for our master’s program. Some of the other program directors were also advising students to look at degree plans. Later, I thought, “Degree plans are not what you should be worried about.”

In our program, I have yet to see a grad student who experienced significant problems because they didn’t take the right classes. I admit our particular degree plan is very unstructured: a couple of core courses and a lot of electives. But registering for classes and taking them is trivial. Barely even counts as an obstacle.

I wondered what were the real obstacles I’ve seen students face in our graduate program. I thought back to students who had not finished their master’s degree in our program. Most fell into one of three categories.

A student thinking about starting a master’s program should worry much more about those pitfalls, not worrying about how many credit hours and class sequences they need. But through inexperience, they probably won’t, meaning it’s going to my job as program director to make them worry about the right things.

Picture by docpop on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

In our program, I have yet to see a grad student who experienced significant problems because they didn’t take the right classes. I admit our particular degree plan is very unstructured: a couple of core courses and a lot of electives. But registering for classes and taking them is trivial. Barely even counts as an obstacle.

I wondered what were the real obstacles I’ve seen students face in our graduate program. I thought back to students who had not finished their master’s degree in our program. Most fell into one of three categories.

- Didn’t want it bad enough. The biggest group of students can complete a grad degree, but drift away without finishing. There are lots of reasons this happens, but they mostly tie to motivation.

- Students got in to grad school for the wrong reasons (i.e., not knowing what else to do) or never clearly articulated to themselves why they were doing this. With no clearly defined goals for themselves, they wander.

- Students have conflicting priorities, and grad school isn’t the top one. They’re employed and working on degrees part-time. They have small children. A job offer comes up.

- Sometimes, it’s just pure fatigue of studying. Or, if you’re not feeling charitable, laziness.

- Couldn’t perform academically. A smaller number of students take themselves out of the program because they can’t maintain their grade point average. It’s hard to tell how many of these are actually in the category above: the root problem is they don’t want it, and it manifests as Cs in grad classes.

- Conflict with supervisor. Thankfully, this is the rarest. Meltdown of the mentoring relationship doesn’t happen often, but it it the hardest to cope with for all concerned. Strictly speaking, we haven’t lost any students because of this, because we’ve had reasonable success in transitioning students to new supervisors so they could finish. But it’s been close.

A student thinking about starting a master’s program should worry much more about those pitfalls, not worrying about how many credit hours and class sequences they need. But through inexperience, they probably won’t, meaning it’s going to my job as program director to make them worry about the right things.

Picture by docpop on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

08 February 2012

From open gaming to open science

I am an academic, not a business person. With the ongoing move to boycott Elsevier, which has gained attention from academic news sources, I asked someone who was in business for his take.

I’ve know Ryan Dancey for about 15 years, from his creation of the game Legend of the Five Rings. He created a business called Five Rings Publishing Group that was sold to Wizards of the Coast. As part of that sale, he was involved in the move of the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game from TSR to Wizards of the Coast.

Just before that sale, TSR had been viewed by players for years a big, greedy corporate publisher. Gamers often referred to it online T$R, which indicated an unhealthy disconnect between the company and their buyers, which reminded me of the disconnect between Elsevier (and other publishers) and scientists and librarians.

Once at Wizards of the Coast, Ryan oversaw the rollout of Dungeons and Dragons Third Edition. For those of you not involved in tabletop role-playing, D&D3 was notable because it was open. The d20 system that D&D had used for years was being given away, for other publishers to use, for free.

The rationale for opening the system was that the biggest strength of D&D was not the rules, or the world, but the number of people who knew how to play the game. Any gamer could go anywhere, and probably find other people who knew how to play D&D. It was less likely that they’d be able to find someone playing some less popular role-playing game, of the hundreds that proliferated over the years. By opening up the rules, players could be drawn in by other kinds of role-playing experiences besides the familiar “dungeon crawl” of D&D, and this would ultimately make D&D stronger in the market.

So Ryan has a few experiences with open versus closed publishing systems.

Ryan also knows a bit more about science than your average guy on the street. The open gaming license came from his understanding of open licenses in computing. Plus, he once told me that he was reading Steve Gould’s mammoth The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (I reviewed it here) for fun. This is not most people’s idea of fun.

I asked Ryan if he thought a publishing company like Elsevier could climb out of the hole it dug itself into.

Posted with Ryan’s permission.

I’ve know Ryan Dancey for about 15 years, from his creation of the game Legend of the Five Rings. He created a business called Five Rings Publishing Group that was sold to Wizards of the Coast. As part of that sale, he was involved in the move of the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game from TSR to Wizards of the Coast.

Just before that sale, TSR had been viewed by players for years a big, greedy corporate publisher. Gamers often referred to it online T$R, which indicated an unhealthy disconnect between the company and their buyers, which reminded me of the disconnect between Elsevier (and other publishers) and scientists and librarians.

Once at Wizards of the Coast, Ryan oversaw the rollout of Dungeons and Dragons Third Edition. For those of you not involved in tabletop role-playing, D&D3 was notable because it was open. The d20 system that D&D had used for years was being given away, for other publishers to use, for free.

The rationale for opening the system was that the biggest strength of D&D was not the rules, or the world, but the number of people who knew how to play the game. Any gamer could go anywhere, and probably find other people who knew how to play D&D. It was less likely that they’d be able to find someone playing some less popular role-playing game, of the hundreds that proliferated over the years. By opening up the rules, players could be drawn in by other kinds of role-playing experiences besides the familiar “dungeon crawl” of D&D, and this would ultimately make D&D stronger in the market.

So Ryan has a few experiences with open versus closed publishing systems.

Ryan also knows a bit more about science than your average guy on the street. The open gaming license came from his understanding of open licenses in computing. Plus, he once told me that he was reading Steve Gould’s mammoth The Structure of Evolutionary Theory (I reviewed it here) for fun. This is not most people’s idea of fun.

I asked Ryan if he thought a publishing company like Elsevier could climb out of the hole it dug itself into.

Sure they can. Remember when Apple was viewed as being ridiculously high-priced without enough value-add to warrant the price premium?

I think the industry has a couple of inter-related problems. First, over many decades an entrenched culture of profit-taking has evolved in the science publishing field. Today you have large companies employing lots of people with stakeholders and shareholders who expect growth and profitability. The need of this industry to thrive has become a tautology - it exists because it exists.

At the same time you have real science being done more rapidly and interactively via things like on-line article repositories and various group chat venues. For the people who think science should be done transparently with full disclosure and communication of data and results, this only makes sense. The original need for the published materials was one:many communication, which was only really feasible using print. Now we have many:many communication facilitated by the internet, the old system has become not only redundant but it is charging a monopoly rent as well.

I think what will happen will be that the scientific community will move (slowly) away from a model where citations from peer-reviewed publications are the indicator of success to one where citations from highly-regarded internet publications replace them. To get there the community needs a reputation economy and a web of trust (although frankly the existing web of trust for peer review seems tissue-thin to and outside observer such as myself).

At the end of the day I wouldn't bet on the survival of any of the existing publishers in their current formats or with their current product line. The publisher that best provides for a transition to a social network-driven science model will likely win the race. Unfortunately, everyone involved is going to suffer the chaos and disruption that always comes with this sort of transition in process.

Were I CEO of Elsevier today I'd be working feverishly to get my business model off of getting paid to publish, and into getting paid for providing the service of managing the social network of the science internet.

Posted with Ryan’s permission.

07 February 2012

Tuesday Crustie: What’s bigger than a giant?

This picture was making the rounds last week after being reported by the BBC:

The BBC did not mention a species name, and the infographic below suggests that it’s an unknown. On the CRUST-L listserver, however, the general agreement was that this was Alicella gigantea, the biggest known amphipod. This is a deep water, rarely seen species.

This infographic prompted Rebecca Watson to quip:

Not a heck of a lot is known about its biology, though all signs point to it being a scavenger. The few times its been photographed, its often been on bait. Its mouth is shaped to take in large bites of food, and about 90% of its innards consists of the midgut. Many of the specimens have been retrieved from the guts of fish, so these animals aren’t big enough to escape predators.

Alicella gigantea is collected in the Atlantic, too. It’s thought that they are the same species, but to my knowledge, no DNA work supports that. Several people on the Crustacean discussion list were explicitly skeptical of the idea that something this wide-ranging would be the same species. Indeed, one person noted that differences between the Atlantic and Pacific populations were noted some time ago.

Alicella gigantea is collected in the Atlantic, too. It’s thought that they are the same species, but to my knowledge, no DNA work supports that. Several people on the Crustacean discussion list were explicitly skeptical of the idea that something this wide-ranging would be the same species. Indeed, one person noted that differences between the Atlantic and Pacific populations were noted some time ago.

References

De Broyer C, Thurston MH. 1987. New Atlantic material and redescription of the type specimens of the giant abyssal amphipod Alicella gigantea Chevreux (Crustacea). Zoologica Scripta 16(4): 335-350. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-6409.1987.tb00079.x

Barnard JL, Ingram CL. 1986. The supergiant amphipod, Alicella gigantea Chevreux from the North Pacific Gyre. Journal of Crustacean Biology 6: 825-839.

The BBC did not mention a species name, and the infographic below suggests that it’s an unknown. On the CRUST-L listserver, however, the general agreement was that this was Alicella gigantea, the biggest known amphipod. This is a deep water, rarely seen species.

This infographic prompted Rebecca Watson to quip:

If you’re wondering how big Superprawn was, this image clearly shows he was about half the size of New Zealand.

Not a heck of a lot is known about its biology, though all signs point to it being a scavenger. The few times its been photographed, its often been on bait. Its mouth is shaped to take in large bites of food, and about 90% of its innards consists of the midgut. Many of the specimens have been retrieved from the guts of fish, so these animals aren’t big enough to escape predators.

References

De Broyer C, Thurston MH. 1987. New Atlantic material and redescription of the type specimens of the giant abyssal amphipod Alicella gigantea Chevreux (Crustacea). Zoologica Scripta 16(4): 335-350. DOI: 10.1111/j.1463-6409.1987.tb00079.x

Barnard JL, Ingram CL. 1986. The supergiant amphipod, Alicella gigantea Chevreux from the North Pacific Gyre. Journal of Crustacean Biology 6: 825-839.

06 February 2012

Death on campus

I was probably just getting into my office this morning when a woman was found dead near the building I work in.

The police are calling the death “questionable.”

I know nothing more than what’s here: the police are investigating, my building is closed, and classes are cancelled today. As I type this, I just saw a tweet that there is no indication that anyone else is in any danger.

I am trying to figure out how it was that I knew nothing until students started sending me text messages asking about class this morning, while I was sitting at my desk with my email open. I went first to the university’s police department website: nothing. I went to the “alerts” link to find today’s date and a directions to check the university’s home page for more details.

There were no more details on the university’s home page.

I checked Twitter. I follow my institution’s Twitter account, but for those mysterious unknown reasons, the tweet had not shown up in my timeline. Checking the university’s Twitter feed finally led me to a link to a Facebook post confirming what my students were asking me.

Only about an hour after students initially contacted me did I see anything official in my inbox. How the alerting system failed to alert me to something like this is worrisome.

Additional, 10:51 am: Initial local newspaper report.

Additional, 11:25 am:

Update, 11:59 am:

On the university’s Facebook page and in my Twitter search the main point of discussion is: “Why doesn’t the university cancel every class and lock down the campus?” I think this reaction is in response to the initial description of the death as “questionable,” with many people making the connection that this means “murder” and not “accident.”

Working on a Storify of this situation.

Update, 4:32 pm: Some faculty were allowed back into the building, under police escort, to retrieve items from offices and check on status of things in labs. There is a very good chance that the building will be closed until at least noon tomorrow, depending on how far the investigation progresses today.

The Pan American student news site has a story releasing “more details,” which are not really any more details. Indeed, it’s slightly weird that they say this was a woman who appeared to be in her 20s, and then:

There are not faculty members in their 20s at our campus. So what they’re probably trying to say is that it’s not clear if she was a member of the university community.

Update, 5:08 pm: Email came in a few minutes ago that the Science building will be closed tomorrow until at least noon.

Update, 6:29 pm: My initial Storify of the reaction to the death.

Update, 8:54 pm: The local newspaper has a reasonable summary of the day’s events. There was no evidence of stabbing or shooting, but some students are still thinking “murder.” Perhaps the main factor in this still being an ongoing investigation is that the woman had no identification.

Update, 7 February 2012: This morning, the woman was identified as a local high school student. The Science building reopened this afternoon, although all classes were still cancelled for the day. There is still no word on autopsy results.

Update, 7 February 2012, 6:02 pm: The woman’s death has been judged to be a suicide. So very, very sad.

Update, 7 February 2012, 10:26 pm: The news article linked to above has been expanded significantly. It’s just a heartbreaking story. She had talked about suicide before, including that very day, and hurt herself. I have continued updating the Storify, where some of the reactions well, do not give me solace.

Photo from here.

The police are calling the death “questionable.”

I know nothing more than what’s here: the police are investigating, my building is closed, and classes are cancelled today. As I type this, I just saw a tweet that there is no indication that anyone else is in any danger.

I am trying to figure out how it was that I knew nothing until students started sending me text messages asking about class this morning, while I was sitting at my desk with my email open. I went first to the university’s police department website: nothing. I went to the “alerts” link to find today’s date and a directions to check the university’s home page for more details.

There were no more details on the university’s home page.

I checked Twitter. I follow my institution’s Twitter account, but for those mysterious unknown reasons, the tweet had not shown up in my timeline. Checking the university’s Twitter feed finally led me to a link to a Facebook post confirming what my students were asking me.

Only about an hour after students initially contacted me did I see anything official in my inbox. How the alerting system failed to alert me to something like this is worrisome.

Additional, 10:51 am: Initial local newspaper report.

Additional, 11:25 am:

Update, 11:59 am:

On the university’s Facebook page and in my Twitter search the main point of discussion is: “Why doesn’t the university cancel every class and lock down the campus?” I think this reaction is in response to the initial description of the death as “questionable,” with many people making the connection that this means “murder” and not “accident.”

Working on a Storify of this situation.

Update, 4:32 pm: Some faculty were allowed back into the building, under police escort, to retrieve items from offices and check on status of things in labs. There is a very good chance that the building will be closed until at least noon tomorrow, depending on how far the investigation progresses today.

The Pan American student news site has a story releasing “more details,” which are not really any more details. Indeed, it’s slightly weird that they say this was a woman who appeared to be in her 20s, and then:

It is not yet clear whether the person is a student or faculty member.

There are not faculty members in their 20s at our campus. So what they’re probably trying to say is that it’s not clear if she was a member of the university community.

Update, 5:08 pm: Email came in a few minutes ago that the Science building will be closed tomorrow until at least noon.

Update, 6:29 pm: My initial Storify of the reaction to the death.

Update, 8:54 pm: The local newspaper has a reasonable summary of the day’s events. There was no evidence of stabbing or shooting, but some students are still thinking “murder.” Perhaps the main factor in this still being an ongoing investigation is that the woman had no identification.

Update, 7 February 2012: This morning, the woman was identified as a local high school student. The Science building reopened this afternoon, although all classes were still cancelled for the day. There is still no word on autopsy results.

Update, 7 February 2012, 6:02 pm: The woman’s death has been judged to be a suicide. So very, very sad.

Update, 7 February 2012, 10:26 pm: The news article linked to above has been expanded significantly. It’s just a heartbreaking story. She had talked about suicide before, including that very day, and hurt herself. I have continued updating the Storify, where some of the reactions well, do not give me solace.

Photo from here.

Be eaten, make glowing fish poo, profit!

Glowing takes energy. Down in the deep ocean, energy is in short supply, so why would bacteria do this? Bacteria don’t have eyes. It’s not like they’re going to be able to use it to find stuff. And these bacteria are not living in another organism, so it’s not as though they’re glowing in some sort of mutual trade with a host.

These bacteria only glow when they’re in large numbers, close together (quorum sensing), however. This gives a clue to what might being going on. A new paper by Zarubin and colleagues conducts several experiments to test the hypothesis that these deep sea bacteria are glowing because they want to be eaten.

You might think getting eaten is not a productive thing to do. The idea is: bacteria light up when they’re in large enough numbers to signal decent food. The bacteria themselves might not be the food, so much as the article they’re attached to.

The bacteria use the insides of their consumers as a way to disperse themselves throughout the ocean. It’s already been shown that a fairly large number of these glowing bacteria can survive passage through the gut. But that alone doesn’t provide enough a strong test of the hypothesis that the bacteria glow to advertise themselves as bait.

First, the team tested whether animals preferred glowing bacteria by putting two bags in a big tank of predators. One bag contained glowing bacteria; another contained same species, but with a mutation that prevented the glowing. Decapod and mysid crustaceans went almost all for the glowing bacteria. But it’s not a universal attractor; copepod crustaceans ignored both bags of bacteria.

Brine shrimp (Artemia) would start to glow after swimming in these bacteria, and their guts started to glow after the shrimp ate the bacteria.In the picture below, you can see Artemia in plain light, and after 30 seconds in the dark. The light is dim, but they do indeed glow.

There is a problem here, though: they switched the species eating the bacteria. They don’t say whether they tested if Artemia were attracted preferentially to the glowing bacteria. You can show a plausible chain of events, but to “close the loop” on this story, you’d have to use the same bacteria eaters all the way through. The authors justify this partly by convenience (Artemia are easy to rear in large numbers) and partly by saying that this allows them to see the effect better. Brine shrimp don’t have escape behaviour. Thus, this removed possible confounds of an interaction between the glowing and any movements caused by escape responses. They also say that one of the mysid species glows after contacting the bacteria. They don’t show data for that, or give any citations, however. Their convenience came at the cost of ecological plausibility.

The glowing Artemia are much more likely to be eaten by fish – about ten times more likely. They tested this by putting Artemia in tanks with ring-tailed cardinal fish (Apogon annularis, pictured), which is nocturnal. And after the cardinalfish eat these brine shrimp, the bacteria do fine. They make it all the way through the fish’s digestive system, and they make the resulting feces also glow (though probably not brightly). The authors also tested the feces of other bacteria eaters – the Artemia and mysids – and they also tend to glow.

The glowing Artemia are much more likely to be eaten by fish – about ten times more likely. They tested this by putting Artemia in tanks with ring-tailed cardinal fish (Apogon annularis, pictured), which is nocturnal. And after the cardinalfish eat these brine shrimp, the bacteria do fine. They make it all the way through the fish’s digestive system, and they make the resulting feces also glow (though probably not brightly). The authors also tested the feces of other bacteria eaters – the Artemia and mysids – and they also tend to glow. What I’d like to see next is some indication of whether the zooplankton are getting any nutritional value from eating these bacteria. Are the bacterial consumers being tricked into wasting time consuming “empty calories” that will just pass through their guts without benefit? If so, why haven’t the zooplankton wised up to this? I mean, how embarrassing would it be to be punked by bacteria? Or is these a “selfish herd” sort of situation, where a small proportion of group members are lost, but the risk to individuals is so low? And is there any manipulation of the plankton behaviour by the bacteria, similar to the way large parasites often work?

Reference

Zarubin M, Belkin S, Ionescu M, Genin A. 2012. Bacterial bioluminescence as a lure for marine zooplankton and fish Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(3): 853-857. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1116683109

Apogon annularis picture from here.

03 February 2012

Jumping spiders still have use for muscles

This is why you typically need two muscles to get things done. Muscles only shorten; if you flex a joint, you can’t expand your muscles to push that joint back to its original position. You have to pull a different muscle, with different insertion points, to get that limb back to where it was. For instance, you have biceps to flex your forearm, and triceps to extend it.

Spiders have always been something of a puzzle, because many of their limb joints have unpaired muscles. This is particularly true of the joints far from the body; the joints close to, and on, the body have more usual paired muscles.

Spiders have always been something of a puzzle, because many of their limb joints have unpaired muscles. This is particularly true of the joints far from the body; the joints close to, and on, the body have more usual paired muscles.On the face of it, this should mean that their joints should only be able to go int one direction. But spiders are agile predators and their limbs are moving back and forth rapidly.

Many spiders use hydraulic pressures to snap their limbs back into position after a muscle has moved it. This has been quite well investigated in a few small species, but Weihmann and colleagues reckoned it was worth re-investigating in a larger spider. They took a big spider species, Ancylomete concolor (pictured), and studied the forces the legs exerted when this spider jumped.

Some of the math and methodology is a little hairy (no pun intended), but this picture helps:

In short, if the spiders are using hydraulics (as small spiders do), the forces from the tip of the leg should be directed forward. If the spiders are mainly using the paired muscles in the joints close to the body, the forces should be directed much more upward.

Wiehmann and company find that their results are much more in line with the jump being powered by muscular contraction than hydraulic pumping. They’re not saying it’s entirely muscle, though, just that muscles are contributing more than the hydraulic factors.

The team briefly takes a stab at the bigger question: why mess around with all the hydraulics in the first place? Why do spiders not have paired muscles all the way through their legs, like sensible insects and crustaceans? Weihmann and company speculate that because spiders are obligate, active predators, that the loss of extensor muscles means that there’s more room for big, powerful flexord muscles – just the things to grab and grapple and subdue prey.

Reference

Weihmann T, Gunther M, Blickhan R. 2012. Hydraulic leg extension is not necessarily the main drive in large spiders. The Journal of Experimental Biology 215(4): 578-583. DOI: 10.1242/jeb.054585

Photo from here.

02 February 2012

Reporting on that non peer reviewed stuff

Brian Kreuger writes about the recent media coverage of the latest findings on the arsenic life:

I have also been shocked, shocked, I say, to see a paper deposited in arXiv being reported around the world by researchers and journalists alike. Nobody commented that it hadn't been accepted in a peer-reviewed journal.

Except I'm not talking about Rosie Redfield’s arsenic life paper.

I'm talking about the reports of faster than light neutrinos from OPERA.

Did we hear howls of outrage from the physics community over the coverage of the story? More like chirping crickets. Physicists were right there in the thick of the discussion.

This is an example of the differing cultures of the fields. Physics has developed a pre-print culture where people stake their claims with manuscripts. Biology has developed a culture where people stake their claims with final publications. But cultures change, and it’s individual cases like this one that provide a lot of the push to change.

Just because biologists normally only make findings public very near the last step in the publication change does not change that anything made public at any stage is fair game for reporting.

Dr. Redfield made her work public earlier than others would have done. Unusual, but I cannot see the ethical issue with reporting on information that she has voluntarily shared. Indeed, if her work does not pass peer review, the reporting that is going on right now can add context to that story.

For that matter, journalists have covered results presented at scientific conferences for decades. I have never heard serious suggestions that conference reporting is unethical.

The arsenic life story itself tells us that because a paper has been peer reviewed does not make it automatically credible to other researchers. Biologists on the whole weren't convinced by the claim.

Reporting on data that has not gone through the peer review process as if it were truth is not responsible journalism.

I have also been shocked, shocked, I say, to see a paper deposited in arXiv being reported around the world by researchers and journalists alike. Nobody commented that it hadn't been accepted in a peer-reviewed journal.

Except I'm not talking about Rosie Redfield’s arsenic life paper.

I'm talking about the reports of faster than light neutrinos from OPERA.

Did we hear howls of outrage from the physics community over the coverage of the story? More like chirping crickets. Physicists were right there in the thick of the discussion.

This is an example of the differing cultures of the fields. Physics has developed a pre-print culture where people stake their claims with manuscripts. Biology has developed a culture where people stake their claims with final publications. But cultures change, and it’s individual cases like this one that provide a lot of the push to change.