After reading Scicurious’s rant about the difficulties of networking, particularly at conferences, I got to thinking. Several people in the comments talked about the intimidation of trying to talk to more senior researchers. Let’s flip it around, look at it from the point of view of the senior researcher and ask what they want to talk about.

What are my favourite conversations to have at scientific conferences?

Conversations that help someone.

I like helping other people at conferences. At the risk of sounding kind of selfish and needy, I want help, too. Help with current projects. Help with ideas for future projects. Help getting publications. Help getting funded. Help figuring out why reviewers hate the manuscript when people at conferences give the project positive feedback.

Maybe a way to start thinking about networking is to ask, “How can I help?” and “What do I need help with?” How can you create opportunities for another person at a conference?

Conversations that simply acknowledge what I do are also high on my list of talks I like to have. A lot of the time, publishing scientific research feels like shouting into a vacuum. My friends and colleagues in my own department don’t read my papers (which is fair, because I rarely read theirs). You think your blog doesn’t get enough comments? Try waiting years for citations to start coming in. When someone that I do not personally know tells me, “I read your paper in this journal,” I just want to take that moment and polish it until it shines like a shiny stone. It doesn’t even matter if they liked the paper; just that they’ve read it is more than enough.

Along those lines, people who says they like my blog is at higher than usual risk of getting hugged on the spot, even if we've never met before and I have no idea of who they are.

But don’t confuse acknowledgment, or even compliments, with flattery. Acknowledgement is genuine; flattery is manipulative. Compliments are sincere; flattery is not. I hate it when someone tries flattery, because it’s usually obvious and clueless. Don’t tell me that you admire my “world famous” work. I know my place in science better than that, and I don’t need my ego stroked.

We’re told to network for the same sort of reasons that we tell undergraduates that they have to learn calculus: “Because it’s worth points and you’ll need it later, trust me.” You need to get something out of it. Let’s abandon the directive that you must network because, well, “You just gotta!”

Networks grow out of conversations. If you take care of the conversations, the network will take care of itself.

What conversations do you want to have at conferences? That’s not a rhetorical question. I genuinely want to know.

30 March 2012

29 March 2012

Science portfolios

I’ve had several reminders this week about the importance of having students do stuff. Not just answer questions.

Rather than having students turn in a series of prescribed assignments, I want to have undergraduate students develop a portfolio of work.

Portfolios are common in the arts. A scientific CV is sort of a portfolio, with publications being the representative works. Publications are just typically looked up rather than looked at. But ultimately, the goal of both is to have a collection of finished, tangible products to show off.

I like the idea of students making something that they can show off a lot. Because ultimately, their potential employers or supervisors they’ll work with after they graduate are going to want someone who can make stuff and deliver it.

The problem is that I’m not quite sure what a portfolio for an undergraduate science student might look like.

I’ve come close to the portfolio idea in my writing classes. I’ve often had students create a blog, with the idea that it might be something they can point to at the end of the semester as an accomplishment. Of course, there’s other kinds of other content that you could create for the Internet; podcasts and videos are obvious choices.

But there my ideas run dry.

What else could an undergraduate create in the course of a semester? Something that at the end of the semester, they could point to and say – maybe even with a little pride – “I made that.”

Picture by Jason Schlachet on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

- This video has a lot of interesting stuff about embodied cognition. We think better when we move. (Hat tip to Julie Dirksen.)

- This video a reminder about how chasing points can kills motivation.

- I have a student trying visual notetaking who’s showing improvement (hat tip to Sunni Brown; for a great introduction of visual notetaking, see here).

Rather than having students turn in a series of prescribed assignments, I want to have undergraduate students develop a portfolio of work.

Portfolios are common in the arts. A scientific CV is sort of a portfolio, with publications being the representative works. Publications are just typically looked up rather than looked at. But ultimately, the goal of both is to have a collection of finished, tangible products to show off.

I like the idea of students making something that they can show off a lot. Because ultimately, their potential employers or supervisors they’ll work with after they graduate are going to want someone who can make stuff and deliver it.

The problem is that I’m not quite sure what a portfolio for an undergraduate science student might look like.

I’ve come close to the portfolio idea in my writing classes. I’ve often had students create a blog, with the idea that it might be something they can point to at the end of the semester as an accomplishment. Of course, there’s other kinds of other content that you could create for the Internet; podcasts and videos are obvious choices.

But there my ideas run dry.

What else could an undergraduate create in the course of a semester? Something that at the end of the semester, they could point to and say – maybe even with a little pride – “I made that.”

Picture by Jason Schlachet on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

28 March 2012

PACE Bioethics 2012

One of the things that made last week absolutely frantic was that the annual PACE ethics conference, It ran during the last half of the week. Any time I didn't have a meeting, I tried to be in the conference. Here's a quick rundown of some of the highlights that I saw.

On Wednesday morning, I introduced one of the keynote speakers, Robin Fuchs-Young. Robin has visited our campus before many times, including once as an REU speaker. She spoke about the evolution of ethical regulations in research, mostly in the United States. One of the recurring themes in her talk was how recent many regulations and policies were. After the talk, she told me that preparing for this presentation that helped her realize that, "We're not doing a very good job of introducing our students to these issues."

This was immediately followed by a panel I was on, titled, "Would you trust a robot surgeon?" This panel was meant to be about fears of new medical technology generally, although it got a bit more focused on the robotic surgery than I initially expected. There was some interesting discussion of the psychology of who adopts new technologies in any endeavor, not just medicine.

I was on the panel because I was saw some parallels between whether people trust medical technology and science denialism. Indeed, one person at the audience started talking about how the use of any new technology should be made by patients weighing the pros and cons. I pointed out that this was a very academic way of looking at things, and people often don't make decisions based purely on information. I noted that arguably the most successful medical technology in history, the only one that has permanently rid the planet of two diseases, is widely distrusted, even by reasonably highly educated people.

In the afternoon, I watched a panel titled, "Ethical Complications of Perpetual Competition." What blew me away was that what seemed to me to be the most obvious potential complication to competing all the way from K-12 to residency - the temptation to cheat - was never mentioned. One of the things that did come out was that there are some big changes planned for medical education. There's some discussion about creating something like a "Medical humanities" major, so that the medical schools do not just have biology and chemistry majors.

I spent late afternoon and early evening chatting with fellow blogger Janet Stemwedel, a.k.a. Doc Freeride. And the rumors are all true: she's just an amazingly cool person.

It's a fascinating experience to meet someone face to face who you're followed online for years. The online persona captures a lot, but not everything. Her blog doesn't always convey her quirky sense of humour, which is abundantly evident face to face. But anyone who says you can't build real dialogue through online interactions is wrong.

We sat and listened to the evening keynote, by local physician Carlos Cardenas. Cardenas's argument was his criterion for judging health policy: anything that interferes in any way with the relationship with the doctor and a patient is bad. While I appreciated that he was trying to emphasize trust and human connections, his point of view undervalued that any physician is a member of a professional community.

On Thursday, I couldn't miss Janet Stemwedel's keynote. Janet gave a great talk about how many biomedical students think that they can avoid worrying about ethical issues by working with materials in a dish. But using Rebecca Skloot's The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks as a guide, she showed that you don't get a pass on ethical dilemmas just because you're working with tissues and cell lines.

A couple of things stood out to me. One was that the ethics got sticky because the list of relevant stakeholders kept expanding, in an unpredictable way. Nobody knew much about DNA when the HeLa cell line was started; it was only much later that genetic technologies brought Henrietta's family back as stakeholders. The other point that Janet made, echoing Robin's from the day before, was how much ethical policies around research are crisis driven. It's fairly common for policies to be created after problems have occurred, rather than being written in anticipation of problems.

The last panel I saw, in the afternoon, concerned violence, particularly against women and vulnerable groups, as a health care problem. More so than the other panels I had watched, this one focused more on local issues and problems. For instance, the local availability of nurses trained to do examinations for sexual assault, and that there is no medical examiner's office in the region.

One undercurrent that I sensed several times though the conference - and maybe I'm reading between the lines too much - was suspicion of government. After the technology panel I sat on, a local nurse got up and was talking local health care, rather enthusiastically. At some point, she talked about what made "us" great was "our freedoms." I think she may have even snuck in a mention of either the founding fathers, the American constitution, or both.

During the competition panel, one phsyician talked about government being in competition wit physicians. In his evening keynote, Cardenas said:

This was a rather surprising claim to me. I can think of plenty of laws that have saved huge numbers of lives. Seat belt legislation. Safety regulations. Restaurant health inspections.

I suspect I raised my eyebrows, too, when someone in the audience at Cardenas's keynote complained that physicians weren't listened to in policy discussions. I'm almost certain my eyebrows crawled up my forehead when this individual said that if they were allowed to, physicians could solve all the problems in about five minutes.

I'm hoping that was meant to be funny. But I'm not sure it was.

I understand frustration with legislators. I've often said I've been surprised by how much Texas lawmakers want to dabble with universities, for instance. But I don't think I would ever say that we professors could solve it all during a coffee break if people would just listen to us.

I kept sort of waiting for someone to jump up and say, "Ron Paul 2012!"

Janet Stemwedel has blogged about her thoughts here. The university's summary is here.

On Wednesday morning, I introduced one of the keynote speakers, Robin Fuchs-Young. Robin has visited our campus before many times, including once as an REU speaker. She spoke about the evolution of ethical regulations in research, mostly in the United States. One of the recurring themes in her talk was how recent many regulations and policies were. After the talk, she told me that preparing for this presentation that helped her realize that, "We're not doing a very good job of introducing our students to these issues."

This was immediately followed by a panel I was on, titled, "Would you trust a robot surgeon?" This panel was meant to be about fears of new medical technology generally, although it got a bit more focused on the robotic surgery than I initially expected. There was some interesting discussion of the psychology of who adopts new technologies in any endeavor, not just medicine.

I was on the panel because I was saw some parallels between whether people trust medical technology and science denialism. Indeed, one person at the audience started talking about how the use of any new technology should be made by patients weighing the pros and cons. I pointed out that this was a very academic way of looking at things, and people often don't make decisions based purely on information. I noted that arguably the most successful medical technology in history, the only one that has permanently rid the planet of two diseases, is widely distrusted, even by reasonably highly educated people.

In the afternoon, I watched a panel titled, "Ethical Complications of Perpetual Competition." What blew me away was that what seemed to me to be the most obvious potential complication to competing all the way from K-12 to residency - the temptation to cheat - was never mentioned. One of the things that did come out was that there are some big changes planned for medical education. There's some discussion about creating something like a "Medical humanities" major, so that the medical schools do not just have biology and chemistry majors.

I spent late afternoon and early evening chatting with fellow blogger Janet Stemwedel, a.k.a. Doc Freeride. And the rumors are all true: she's just an amazingly cool person.

It's a fascinating experience to meet someone face to face who you're followed online for years. The online persona captures a lot, but not everything. Her blog doesn't always convey her quirky sense of humour, which is abundantly evident face to face. But anyone who says you can't build real dialogue through online interactions is wrong.

We sat and listened to the evening keynote, by local physician Carlos Cardenas. Cardenas's argument was his criterion for judging health policy: anything that interferes in any way with the relationship with the doctor and a patient is bad. While I appreciated that he was trying to emphasize trust and human connections, his point of view undervalued that any physician is a member of a professional community.

On Thursday, I couldn't miss Janet Stemwedel's keynote. Janet gave a great talk about how many biomedical students think that they can avoid worrying about ethical issues by working with materials in a dish. But using Rebecca Skloot's The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks as a guide, she showed that you don't get a pass on ethical dilemmas just because you're working with tissues and cell lines.

A couple of things stood out to me. One was that the ethics got sticky because the list of relevant stakeholders kept expanding, in an unpredictable way. Nobody knew much about DNA when the HeLa cell line was started; it was only much later that genetic technologies brought Henrietta's family back as stakeholders. The other point that Janet made, echoing Robin's from the day before, was how much ethical policies around research are crisis driven. It's fairly common for policies to be created after problems have occurred, rather than being written in anticipation of problems.

The last panel I saw, in the afternoon, concerned violence, particularly against women and vulnerable groups, as a health care problem. More so than the other panels I had watched, this one focused more on local issues and problems. For instance, the local availability of nurses trained to do examinations for sexual assault, and that there is no medical examiner's office in the region.

One undercurrent that I sensed several times though the conference - and maybe I'm reading between the lines too much - was suspicion of government. After the technology panel I sat on, a local nurse got up and was talking local health care, rather enthusiastically. At some point, she talked about what made "us" great was "our freedoms." I think she may have even snuck in a mention of either the founding fathers, the American constitution, or both.

During the competition panel, one phsyician talked about government being in competition wit physicians. In his evening keynote, Cardenas said:

(N)ot one insurance plan ever cured a patient, much less held their hand, and no set of laws written by policy makers in Washington or Austin ever truly saved a life(.)

This was a rather surprising claim to me. I can think of plenty of laws that have saved huge numbers of lives. Seat belt legislation. Safety regulations. Restaurant health inspections.

I suspect I raised my eyebrows, too, when someone in the audience at Cardenas's keynote complained that physicians weren't listened to in policy discussions. I'm almost certain my eyebrows crawled up my forehead when this individual said that if they were allowed to, physicians could solve all the problems in about five minutes.

I'm hoping that was meant to be funny. But I'm not sure it was.

I understand frustration with legislators. I've often said I've been surprised by how much Texas lawmakers want to dabble with universities, for instance. But I don't think I would ever say that we professors could solve it all during a coffee break if people would just listen to us.

I kept sort of waiting for someone to jump up and say, "Ron Paul 2012!"

Janet Stemwedel has blogged about her thoughts here. The university's summary is here.

27 March 2012

Prepare yourself

If you are a researcher, you have only until the end of this week to sign up for round 2 of the #SciFund Challenge! Go here to sign up!

Last time, SciFund raised $75,510 dollars, and ten out of 49 projects met or exceeded their funding goals. And it was pretty darn fun.

Round two of SciFund will run through May!

Tuesday Crustie: Smorgasbord

Decisions, decisions... what kind of crustacean to feature on the Tuesday Crustie feature today?

I choose not to decide!

I don’t recognize the exact species, but I recognize a few cousins to species I’ve studied.

Photo by hyperion327 on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

I choose not to decide!

I don’t recognize the exact species, but I recognize a few cousins to species I’ve studied.

Photo by hyperion327 on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

25 March 2012

More accusations of professor laziness

Aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaand it’s yet another piece claiming that professors are lazy, this time from the Washington Post.

Here's the crux of the argument: Professors at research universities work hard, but we all “know” that only a tiny fraction of universities actually do research, and those people don’t work hard enough (emphasis added).

Speaking as someone at a state university, we have research expectations. And they’re increasing. Indeed, it is arguably more difficult and time consuming to conduct research at an institution with a history of being primarily teaching, because there is less infrastructure and support.

To say that only a tiny number of universities should conduct research is a huge waste of talent and opportunity. Indeed, one of the things that we should be teaching our students is how to conduct research, which requires working individually with students. One of the side effects of these kinds of proposals is that they enhance the Matthew effect at universities: big research universities protect their turf and accumulate more resources, prestige and opportunity, while other universities – and the communities they serve – get less and less done.

And, not surprisingly, the amount of teaching expected does scale with research expectations. Teachers at an emerging research institution like my own teach less than at a community college, but more than a research intensive institution.

There’s a more subtle bias, here, too. It’s the notion that researchers are worth more. Teaching isn’t being valued. Yes, this is couched in terms that researchers put in more hours. However, this editorial provides no evidence that researchers at highly intensive research institutions work more hours than instructors at community colleges and state universities.

The article continues a fine tradition of underestimating the time it takes to prepare and grade students.

Unlikely? In many classes, particularly more advanced classes, the time spent preparing and grading can easily exceed the time in front of a class several times over.

The article also overestimates some of the advantages of being a professor. According to Levy’s piece, professors not only get tenure and “light” teaching loads but “long vacations and sabbaticals.”

By long vacations, I am guessing the author means “summer.” Do you know most academics get nine month appointments? We don’t get paid for summer, unless we teach in summer 9which at our institution is a separate budget and not guaranteed).

I have never had a sabbatical. In my entire department of about twenty faculty, exactly one professor in our department has had a sabbatical. To get that, he sought and received an external grant to pay for it. (And the program is limited to American citizens, so I am not eligible to try for it. But I’m not bitter.)

The other issue with looking at wages of people at the very end of their careers is that it overlooks that training to be a professor takes a long time. In my case, I was in training for over 15 years. There needs to be some acknowledgement of compensation over the course of a career, not just at the very end of a career, with what “top” (most senior) professors earn.

It’s also noteworthy that part of this editorial’s “advantage” of increasing workload is that we would need fewer professors, just in a time when there is a job shortage.

Additional: More discussion from Kristina Killgrove on G+.

More additional, 26 March 2012: Janet Stemwedel, College Guide (with data showing professors are not responsible for driving up tuition costs), and Gin and Tacos.

Hat tip to Neuropolarbear for harshing my mellow on a Sunday morning. Thanks to Scicurious and Katiesci and Cedar Reiner and Kari and other folks for Twitter discussions.

Here's the crux of the argument: Professors at research universities work hard, but we all “know” that only a tiny fraction of universities actually do research, and those people don’t work hard enough (emphasis added).

The faculties of research universities are at the center of America’s progress in intellectual, technological and scientific pursuits, and there should be no quarrel with their financial rewards or schedules. In fact, they often work hours well beyond those of average non-academic professionals.

Unfortunately, the salaries and the workloads applied to the highest echelons of faculty have been grafted onto colleges whose primary mission is teaching, not research. These include many state colleges, virtually all community colleges and hundreds of private institutions.

Speaking as someone at a state university, we have research expectations. And they’re increasing. Indeed, it is arguably more difficult and time consuming to conduct research at an institution with a history of being primarily teaching, because there is less infrastructure and support.

To say that only a tiny number of universities should conduct research is a huge waste of talent and opportunity. Indeed, one of the things that we should be teaching our students is how to conduct research, which requires working individually with students. One of the side effects of these kinds of proposals is that they enhance the Matthew effect at universities: big research universities protect their turf and accumulate more resources, prestige and opportunity, while other universities – and the communities they serve – get less and less done.

And, not surprisingly, the amount of teaching expected does scale with research expectations. Teachers at an emerging research institution like my own teach less than at a community college, but more than a research intensive institution.

There’s a more subtle bias, here, too. It’s the notion that researchers are worth more. Teaching isn’t being valued. Yes, this is couched in terms that researchers put in more hours. However, this editorial provides no evidence that researchers at highly intensive research institutions work more hours than instructors at community colleges and state universities.

The article continues a fine tradition of underestimating the time it takes to prepare and grade students.

Even in the unlikely event that they devote an equal amount of time to grading and class preparation...

Unlikely? In many classes, particularly more advanced classes, the time spent preparing and grading can easily exceed the time in front of a class several times over.

The article also overestimates some of the advantages of being a professor. According to Levy’s piece, professors not only get tenure and “light” teaching loads but “long vacations and sabbaticals.”

By long vacations, I am guessing the author means “summer.” Do you know most academics get nine month appointments? We don’t get paid for summer, unless we teach in summer 9which at our institution is a separate budget and not guaranteed).

I have never had a sabbatical. In my entire department of about twenty faculty, exactly one professor in our department has had a sabbatical. To get that, he sought and received an external grant to pay for it. (And the program is limited to American citizens, so I am not eligible to try for it. But I’m not bitter.)

The other issue with looking at wages of people at the very end of their careers is that it overlooks that training to be a professor takes a long time. In my case, I was in training for over 15 years. There needs to be some acknowledgement of compensation over the course of a career, not just at the very end of a career, with what “top” (most senior) professors earn.

It’s also noteworthy that part of this editorial’s “advantage” of increasing workload is that we would need fewer professors, just in a time when there is a job shortage.

Additional: More discussion from Kristina Killgrove on G+.

More additional, 26 March 2012: Janet Stemwedel, College Guide (with data showing professors are not responsible for driving up tuition costs), and Gin and Tacos.

Hat tip to Neuropolarbear for harshing my mellow on a Sunday morning. Thanks to Scicurious and Katiesci and Cedar Reiner and Kari and other folks for Twitter discussions.

23 March 2012

The Zen of Presentations, Part 53: Doing it vs. talking about it

When you are in the thick of a project, the time you spend getting stuff done might look like this.

Because of how much time you have spent learning that technique, getting some initial preliminary results, then having it mysteriously fail for no reason, troubleshooting, learning that your boss calls part of the technique “black voodoo magic”, offering sacrifices to the lab gods, it is understandable that when you are given the chance to talk about that research... you spend the same amount of time describing those techniques.

I think this is particularly a trap for people who are just coming into a project. When I learned a new technique, I was so excited about this technique giving me my first data that I focused too much on the technique, and not enough on the data.

It’s worth noting that in research articles, the methods section is often set in small text or placed last in the article, after the conclusions. Both of these are good indications that descriptions of techniques and methodologies are fine print. Relatively few people are going to be tremendously excited by how you optimised your buffers, or found a great way to manipulate data in Excel.

The breakdown might look more like this.

Many presentations jump into the details way too fast. A lot of good technical presentations are characterized by long introductions. Having an introduction take up half your talk is not out of the question. The data that answers a question and what you conclude about it should make up most of the rest.

The time you spend talking about stuff you did in your project need not – indeed, should not – bear much relationship to the amount of time you spent on that task.

Related posts

Poster Venn (Better Posters blog)

Because of how much time you have spent learning that technique, getting some initial preliminary results, then having it mysteriously fail for no reason, troubleshooting, learning that your boss calls part of the technique “black voodoo magic”, offering sacrifices to the lab gods, it is understandable that when you are given the chance to talk about that research... you spend the same amount of time describing those techniques.

I think this is particularly a trap for people who are just coming into a project. When I learned a new technique, I was so excited about this technique giving me my first data that I focused too much on the technique, and not enough on the data.

It’s worth noting that in research articles, the methods section is often set in small text or placed last in the article, after the conclusions. Both of these are good indications that descriptions of techniques and methodologies are fine print. Relatively few people are going to be tremendously excited by how you optimised your buffers, or found a great way to manipulate data in Excel.

The breakdown might look more like this.

Many presentations jump into the details way too fast. A lot of good technical presentations are characterized by long introductions. Having an introduction take up half your talk is not out of the question. The data that answers a question and what you conclude about it should make up most of the rest.

The time you spend talking about stuff you did in your project need not – indeed, should not – bear much relationship to the amount of time you spent on that task.

Related posts

Poster Venn (Better Posters blog)

21 March 2012

The myth of fingerprints

Could you have made a mistake?

If you are a fingerprint examiner in court giving testimony, the answer was once, “No,” according to Mnookin (2001).

(I’ve been unable to find is this is still true.)

A new paper by Ulery and colleagues is a follow-up to a paper they published last year on fingerprint analysis. The previous paper found 85% of fingerprint examiners made mistakes where two fingerprints were judged to be from different people, when in fact they were from the same person (false negative). There was much more analysis, but you get the idea.

A new paper by Ulery and colleagues is a follow-up to a paper they published last year on fingerprint analysis. The previous paper found 85% of fingerprint examiners made mistakes where two fingerprints were judged to be from different people, when in fact they were from the same person (false negative). There was much more analysis, but you get the idea.

The researchers wanted to see how consistent the decisions were after time had passed. For this paper, they used some of the same fingerprint examiners that had been tested before (72 of 169 from he previous paper). It had been seven months since the fingerprint examiners had seen these prints. They were all prints that they’d seen for the previous research, but Ulery and colleagues didn’t tell them that.

Because the experimenters wanted to see if examiners who had made a mistake before would make the same mistakes again, the choice of what pairs of fingerprints to make was somewhat complicated. But all examiners saw nine pairs fingerprints that were not matched (from different people) and sixteen pairs that were matched (same people). And it’s also important to note that the fingerprints chosen were chosen in part because they were difficult.

In the original test, the fingerprint examiners only rarely said two fingerprints were from the same person when they weren’t (false positives). On the retest, there were no cases of false positives, either repeated mistakes from the previous test or entirely new mistakes.

The reverse mistake, the false negatives, were more common. Of the false negative errors made in the previous paper, about 30% were made again in the new study. And the examiners made new mistakes that hadn’t been made before.

There is some good news here, however. One piece of good news in this paper is that in some cases the examiners’ ratings of the difficulty were correlated with probability they would make the same decisions as before. But he examiner’s ratings of difficulty, however, only weakly predicted the errors that they made.

Another important finding is evidence that the best way to reduce errors is to have fingerprints examined by multiple people, rather than multiple examinations by the same person. The authors write:

Nevertheless, even with two examiners checking fingerprints, Ulery and colleagues estimate that 19% of false negatives would not be picked out by having another examiner check the prints.

These papers all concern decisions made by experts, which is obviously the logical place to start from a policy and pragmatic point of view. As an exercise in seeing how expertise develops, tt would be interesting to see if beginners showed the same types of patterns in decision making.

References

Mookin JL. 2001. Fingerprint evidence in an age of DNA profiling. Brooklyn Law Review 67: 13.

Saks M. (2005). The coming paradigm shift in forensic identification science Science, 309 (5736), 892-895 DOI: 10.1126/science.1111565

Ulery B, Hicklin R, Buscaglia J, & Roberts M (2012). Repeatability and Reproducibility of Decisions by Latent Fingerprint Examiners PLoS ONE, 7 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032800

Photo by Vince Alongi on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

If you are a fingerprint examiner in court giving testimony, the answer was once, “No,” according to Mnookin (2001).

(T)he primary professional organization for fingerprint examiners, the International Association for Identification, passed a resolution in 1979 making it professional misconduct for any fingerprint examiner to provide courtroom testimony that labeled a match “possible, probable or likely” rather than “certain.”

(I’ve been unable to find is this is still true.)

The researchers wanted to see how consistent the decisions were after time had passed. For this paper, they used some of the same fingerprint examiners that had been tested before (72 of 169 from he previous paper). It had been seven months since the fingerprint examiners had seen these prints. They were all prints that they’d seen for the previous research, but Ulery and colleagues didn’t tell them that.

Because the experimenters wanted to see if examiners who had made a mistake before would make the same mistakes again, the choice of what pairs of fingerprints to make was somewhat complicated. But all examiners saw nine pairs fingerprints that were not matched (from different people) and sixteen pairs that were matched (same people). And it’s also important to note that the fingerprints chosen were chosen in part because they were difficult.

In the original test, the fingerprint examiners only rarely said two fingerprints were from the same person when they weren’t (false positives). On the retest, there were no cases of false positives, either repeated mistakes from the previous test or entirely new mistakes.

The reverse mistake, the false negatives, were more common. Of the false negative errors made in the previous paper, about 30% were made again in the new study. And the examiners made new mistakes that hadn’t been made before.

There is some good news here, however. One piece of good news in this paper is that in some cases the examiners’ ratings of the difficulty were correlated with probability they would make the same decisions as before. But he examiner’s ratings of difficulty, however, only weakly predicted the errors that they made.

Another important finding is evidence that the best way to reduce errors is to have fingerprints examined by multiple people, rather than multiple examinations by the same person. The authors write:

Much of the observed lack of reproducibility is associated with prints on which individual examiners were not consistent, rather than persistent differences among examiners.

Nevertheless, even with two examiners checking fingerprints, Ulery and colleagues estimate that 19% of false negatives would not be picked out by having another examiner check the prints.

These papers all concern decisions made by experts, which is obviously the logical place to start from a policy and pragmatic point of view. As an exercise in seeing how expertise develops, tt would be interesting to see if beginners showed the same types of patterns in decision making.

References

Mookin JL. 2001. Fingerprint evidence in an age of DNA profiling. Brooklyn Law Review 67: 13.

Saks M. (2005). The coming paradigm shift in forensic identification science Science, 309 (5736), 892-895 DOI: 10.1126/science.1111565

Ulery B, Hicklin R, Buscaglia J, & Roberts M (2012). Repeatability and Reproducibility of Decisions by Latent Fingerprint Examiners PLoS ONE, 7 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032800

Photo by Vince Alongi on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

20 March 2012

Tuesday Crustie: Celebration!

Various species. Their identity uncertain, but they seem to represent caridian shrimps, and anomuran crabs and squat lobsters (too few large legs on the ones in the upper right and lower left to be astacideans or brachyurans).

Photo by Wyrmworld on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

Photo by Wyrmworld on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

16 March 2012

The nano scale, fingernails, and using yourself as a research subject

A nanometer is one billionth of a meter. It’s hard to visualize something that small. To try to put it in understandable terms, Robyn Williams said this on The Science Show (I think).

And for some reason, that little claim stuck with me. I kept wondering, “Is that accurate?”

Last fall, I asked students in my Biological Writing class to estimate how much time it would take for fingernails to grow one nanometer. We had talked about Fermi problems in class, using some examples in the book Guesstimation: Solving the World's Problems on the Back of a Cocktail Napkin (Amazon). Out of 13 estimates, eleven ranged from 0.09 to 1.6 seconds, and I had two outliers of 60 and 600 seconds.

Last fall, I asked students in my Biological Writing class to estimate how much time it would take for fingernails to grow one nanometer. We had talked about Fermi problems in class, using some examples in the book Guesstimation: Solving the World's Problems on the Back of a Cocktail Napkin (Amazon). Out of 13 estimates, eleven ranged from 0.09 to 1.6 seconds, and I had two outliers of 60 and 600 seconds.

But estimates just weren’t good enough. I wanted real data. When the new year came, the next time I trimmed my fingernails, I opened up a spreadsheet and wrote down the date. When I needed to cut them again a few weeks later, I got out calipers that could measure to 0.01 mm. I measured each fingernail at three points to get an average rate of growth and to even out irregularities from my cutting the nails.

I was going to measure the rate of growth (nanometers per second) five times. I managed to fracture a couple of my nails at one point, making correct measures of length tricky for them, so I went another time. I ended up with five or six measures of growth rate for ten fingers.

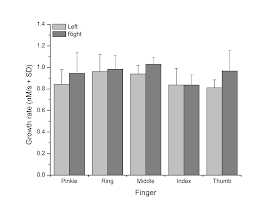

The results of my somewhat obsessive self-study:

An average fingernail growth rate of 0.92 nM / sec. My Biological Writing students had come up with quite decent estimates – certainly better than you’d get by just guessing! The mode estimate from the class was that it would take about one second for a fingernail to grow one nanometer.

I was a bit surprised to see that growth isn’t as even as I might have expected. It fit my subjective impressions that the ring fingernails looked like they needed trimming first, though I wouldn't have expected the middle fingernail was growing just as fast.

Getting back to the original claim, we need not only the rate of growth, but the time of the sentence. It took me about 3.77 second to say, “By the time you finish this sentence, your fingernails will have grown one nanometer” (n = 10, timed with stopwatch).

This means that the original claim is quite conservative! By the time you finish saying that sentence out loud, your fingernails will probably have grown something like three and a half nanometers (3.47 nM, if you wanted to be precise), not just one.

By the time you finish this sentence, your fingernails will have grown one nanometer.

And for some reason, that little claim stuck with me. I kept wondering, “Is that accurate?”

Last fall, I asked students in my Biological Writing class to estimate how much time it would take for fingernails to grow one nanometer. We had talked about Fermi problems in class, using some examples in the book Guesstimation: Solving the World's Problems on the Back of a Cocktail Napkin (Amazon). Out of 13 estimates, eleven ranged from 0.09 to 1.6 seconds, and I had two outliers of 60 and 600 seconds.

Last fall, I asked students in my Biological Writing class to estimate how much time it would take for fingernails to grow one nanometer. We had talked about Fermi problems in class, using some examples in the book Guesstimation: Solving the World's Problems on the Back of a Cocktail Napkin (Amazon). Out of 13 estimates, eleven ranged from 0.09 to 1.6 seconds, and I had two outliers of 60 and 600 seconds.But estimates just weren’t good enough. I wanted real data. When the new year came, the next time I trimmed my fingernails, I opened up a spreadsheet and wrote down the date. When I needed to cut them again a few weeks later, I got out calipers that could measure to 0.01 mm. I measured each fingernail at three points to get an average rate of growth and to even out irregularities from my cutting the nails.

I was going to measure the rate of growth (nanometers per second) five times. I managed to fracture a couple of my nails at one point, making correct measures of length tricky for them, so I went another time. I ended up with five or six measures of growth rate for ten fingers.

The results of my somewhat obsessive self-study:

An average fingernail growth rate of 0.92 nM / sec. My Biological Writing students had come up with quite decent estimates – certainly better than you’d get by just guessing! The mode estimate from the class was that it would take about one second for a fingernail to grow one nanometer.

I was a bit surprised to see that growth isn’t as even as I might have expected. It fit my subjective impressions that the ring fingernails looked like they needed trimming first, though I wouldn't have expected the middle fingernail was growing just as fast.

Getting back to the original claim, we need not only the rate of growth, but the time of the sentence. It took me about 3.77 second to say, “By the time you finish this sentence, your fingernails will have grown one nanometer” (n = 10, timed with stopwatch).

This means that the original claim is quite conservative! By the time you finish saying that sentence out loud, your fingernails will probably have grown something like three and a half nanometers (3.47 nM, if you wanted to be precise), not just one.

15 March 2012

The anti-calm poster

This one is Becca’s fault...

More appropriate for those in grad school, tenure track... academia generally.

More appropriate for those in grad school, tenure track... academia generally.

Comments for first half of March, 2012

Scicurious offers advice on writing a dissertation.

Jason Snyder looks at differences in citation report databases.

What’s the craziest thing you’ve done for science?

io9 reports on science crowdfunding.

The Cellular Scale looks at action potentials in an iconic meat eating... plant.

Jason Snyder looks at differences in citation report databases.

What’s the craziest thing you’ve done for science?

io9 reports on science crowdfunding.

The Cellular Scale looks at action potentials in an iconic meat eating... plant.

14 March 2012

Calling South Texans!

Have you seen the items in this gentleman’s hands?

Whale shark researcher Dr. Al Dove reports that these GOS tags have been found near Brownsville, Texas. He would like them back!

If you are a local here in South Texas, please help spread the word. If you get them, send him a tweet: he’s @para_sight on Twitter.

Additional, 16 March 2012: This was featured on one local television station’s evening news broadcast. I’m glad the story spread, though we are still looking for these!

Whale shark researcher Dr. Al Dove reports that these GOS tags have been found near Brownsville, Texas. He would like them back!

If you are a local here in South Texas, please help spread the word. If you get them, send him a tweet: he’s @para_sight on Twitter.

Additional, 16 March 2012: This was featured on one local television station’s evening news broadcast. I’m glad the story spread, though we are still looking for these!

The Zen of Presentations, Part 52: Big finish

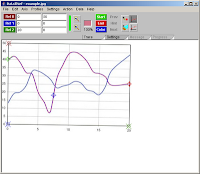

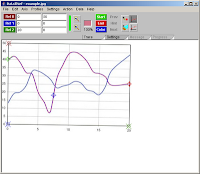

Two people go in for a rather invasive and somewhat painful surgical procedure. The nature of the procedure means that the can’t be anesthetized. To keep track of their pain, the physicians ask the patients to rate the level of pain they’re experiencing at regular intervals, from one to ten. Imagine this is charted below.

When the red line hits “0”, it’s because the procedure was done.

Some months later, on a follow-up, the patients are asked to describe their overall experience.

You would expect the patient whose responses that are plotted in blue in the chart above would report the experience being much worse. If you add all the numbers, this person’s average pain was higher, and they were in pain for much longer.

The patient whose responses are in red usually reports the experience being much worse than the patient whose responses are in blue, even though this person’s procedure was shorter, and they were in less pain overall. Why?

Endings matter.

The entire experience is profoundly influenced by that last memory. The patient in red ends in almost excruciating pain; the patient in blue ends with mild discomfort. And that last experience tends to be one that sticks.

This might explain why twist endings in movies and television and other stories are so divisive. They can be spectacularly successful or agonizingly bad. Sometimes a great ending saves an movie or episode and turns the run-of-the-mill into something quite amazing (e.g., The Sixth Sense). How many times have you been going alone, carried along with a story... and the ending ruins it, and you leave with a sour taste in your mouth? (E.g., Jacob’s Ladder.)

This talk - the most popular Ignite! talk to date - could be significantly improved:

This talk is popular because it is so useful. But the ending... a recap? What do you need a recap in a five minute talk for? Peoples’ memories aren’t that bad.

Nancy Duarte nailed what an ending should be in her book Resonate: a vision for a better tomorrow. She calls it, “the new bliss.” The new bliss sets out what could be, if the audience takes the story you have told them and acts on it.

Here’s a great example of an ending that lays out a new bliss. It’s Hans Rosling talking about the magic of washing machines:

A world with washing machines is not just a world with clean laundry. A world with washing machines is a world where machines have freed up time for parents to read books to their children.

In a scientific talk, the new bliss can be something as simple as a more complete understanding of some fine theoretic point that people in your field will appreciate. It could be ruling out an hypothesis. Or it could be a shifted paradigm. Or maybe there are big potential practical spin-offs that could come out of the work.

Put a lot of work into your endings.

Note: I heard the patient story on an online video somewhere; I thought it was on the TED website, but can’t find it gain. If anyone recognizes this and can point me to it, I would be most grateful!

When the red line hits “0”, it’s because the procedure was done.

Some months later, on a follow-up, the patients are asked to describe their overall experience.

You would expect the patient whose responses that are plotted in blue in the chart above would report the experience being much worse. If you add all the numbers, this person’s average pain was higher, and they were in pain for much longer.

The patient whose responses are in red usually reports the experience being much worse than the patient whose responses are in blue, even though this person’s procedure was shorter, and they were in less pain overall. Why?

Endings matter.

The entire experience is profoundly influenced by that last memory. The patient in red ends in almost excruciating pain; the patient in blue ends with mild discomfort. And that last experience tends to be one that sticks.

This might explain why twist endings in movies and television and other stories are so divisive. They can be spectacularly successful or agonizingly bad. Sometimes a great ending saves an movie or episode and turns the run-of-the-mill into something quite amazing (e.g., The Sixth Sense). How many times have you been going alone, carried along with a story... and the ending ruins it, and you leave with a sour taste in your mouth? (E.g., Jacob’s Ladder.)

This talk - the most popular Ignite! talk to date - could be significantly improved:

This talk is popular because it is so useful. But the ending... a recap? What do you need a recap in a five minute talk for? Peoples’ memories aren’t that bad.

Nancy Duarte nailed what an ending should be in her book Resonate: a vision for a better tomorrow. She calls it, “the new bliss.” The new bliss sets out what could be, if the audience takes the story you have told them and acts on it.

Here’s a great example of an ending that lays out a new bliss. It’s Hans Rosling talking about the magic of washing machines:

A world with washing machines is not just a world with clean laundry. A world with washing machines is a world where machines have freed up time for parents to read books to their children.

In a scientific talk, the new bliss can be something as simple as a more complete understanding of some fine theoretic point that people in your field will appreciate. It could be ruling out an hypothesis. Or it could be a shifted paradigm. Or maybe there are big potential practical spin-offs that could come out of the work.

Put a lot of work into your endings.

Note: I heard the patient story on an online video somewhere; I thought it was on the TED website, but can’t find it gain. If anyone recognizes this and can point me to it, I would be most grateful!

13 March 2012

Tuesday Crustie: Headline news

Because really, kids should be getting IACUC training much earlier.

Okay, this is a cheat: there is no actual crustacean in this picture. But I love this headline too much. Better without context.

Photo by Gerry Balding on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

12 March 2012

Neuroscientists Talk Shop

When I was at the University of Texas San Antonio last week, I recorded an interview with them for their Neuroscientists Talk Shop podcast. Mine is now up. It’s mostly about nociception, although the connectome post I published last week also came up.

In this interview, my co-author on the nociception paper, Sakshi Puri, talks a bit about getting emails from PETA. When we published our paper, I blogged about my worries that there would be some people who would not like it regardless of what the paper actually says. I was disappointed to learn I was right, after the amount of effort we put into the paper to prevent misunderstandings.

For the record, if any of you have a problem with my research, please include me in that conversation.

There are 80 other interviews in this series. For fellow neuroethologists, some that might be particularly interesting include:

Mine was so enjoyable and the questions were so good, I plan go back and listen to a lot of episodes in their back catalog.

In this interview, my co-author on the nociception paper, Sakshi Puri, talks a bit about getting emails from PETA. When we published our paper, I blogged about my worries that there would be some people who would not like it regardless of what the paper actually says. I was disappointed to learn I was right, after the amount of effort we put into the paper to prevent misunderstandings.

For the record, if any of you have a problem with my research, please include me in that conversation.

There are 80 other interviews in this series. For fellow neuroethologists, some that might be particularly interesting include:

- David Perkel on bird song

- Karen Bales on primate bonding

- Peter Narins on acoustic communication

- Mike Smotherman on bat vocalizations

- Suzana Herculano-Houzel on comparative brain sizes

- Brenton Cooper on bird song development

Mine was so enjoyable and the questions were so good, I plan go back and listen to a lot of episodes in their back catalog.

09 March 2012

UTSA talk

On Wednesday, I drove up to San Antonio to give a talk and meet the fine folks in the University of Texas San Antonio neuroscience group. Because I had decided to talk about nociception, Sakshi Puri came along with me. We got to San Antonio early enough Wednesday that we were able to play a little hooky, and decided that it was a lovely day to go to the zoo. We saw this massive guy there:

Biggest snapping turtle I have ever seen. It looked like it was a million years old.

Thursday went very well. We met lots of people who were doing interesting science but who weren’t waaaaay into themselves. My feature talk was well received, had a mini-Tweet-up (one person who was following me from the Ecology meeting last summer!), followed by lunch with students.

We then recorded an interview of Neuroscientists Talk Shop. My interview isn’t up yet; I’ll let you know when it it. But there are plenty of other interviews there for the neurocurious (76, I think). Just the thing to keep your mind working through an exercise routine, say! We talked about nociception and yesterday’s connectome post.

One of the unexpected things I learned on this trip from my host, Todd Troyer: How to catch a zebra finch.

If a zebra finch escapes in your room, wait until it lands. Note where it is. Then turn off the lights, and reach and grab where it was.

These guys completely shut down when the light goes out. In a room full of chattering birds, the silence was so sudden when we flipped the light switch out that it seemed as though the switch was connected to the birds and the lights both. I just couldn’t get over how immediate and complete the silence was, and how quickly they started up again when the lights went back on.

After the visits, we went to The Monterey Restaurant. The website does not at all convey the great, funky feeling of the place. It also features the most... different... desert I think I have ever had: the cheese-plate pop-tart. It’s a slightly surreal combination of sweetness and, well, cheese. I was glad that I had it, because it was a taste unlike any other I can ever remember experiencing. I’m not sure I would order it again.

Thanks to all the students and faculty at UTSA for making it such a fun day for us!

Biggest snapping turtle I have ever seen. It looked like it was a million years old.

Thursday went very well. We met lots of people who were doing interesting science but who weren’t waaaaay into themselves. My feature talk was well received, had a mini-Tweet-up (one person who was following me from the Ecology meeting last summer!), followed by lunch with students.

We then recorded an interview of Neuroscientists Talk Shop. My interview isn’t up yet; I’ll let you know when it it. But there are plenty of other interviews there for the neurocurious (76, I think). Just the thing to keep your mind working through an exercise routine, say! We talked about nociception and yesterday’s connectome post.

One of the unexpected things I learned on this trip from my host, Todd Troyer: How to catch a zebra finch.

If a zebra finch escapes in your room, wait until it lands. Note where it is. Then turn off the lights, and reach and grab where it was.

These guys completely shut down when the light goes out. In a room full of chattering birds, the silence was so sudden when we flipped the light switch out that it seemed as though the switch was connected to the birds and the lights both. I just couldn’t get over how immediate and complete the silence was, and how quickly they started up again when the lights went back on.

After the visits, we went to The Monterey Restaurant. The website does not at all convey the great, funky feeling of the place. It also features the most... different... desert I think I have ever had: the cheese-plate pop-tart. It’s a slightly surreal combination of sweetness and, well, cheese. I was glad that I had it, because it was a taste unlike any other I can ever remember experiencing. I’m not sure I would order it again.

Thanks to all the students and faculty at UTSA for making it such a fun day for us!

08 March 2012

Overselling the connectome

In the last few years, there has been much discussion about the prospect of tracking the neural connections of mammalian, and particularly human, brains at very high levels of detail. Following the concept of a genome – every gene in an organism – a connectome is a map of every anatomical connection between every neuron in an organism.

One of the major proponents of this effort has been Sebastian Seung, who you can see giving a TED talk here. He sells the idea that understanding the human connectome will help us understand human identity. In his talk, Seung encourages his audience to say along with him. “I am my connectome.” He’s written a new book on this subject, Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are.

One of the major proponents of this effort has been Sebastian Seung, who you can see giving a TED talk here. He sells the idea that understanding the human connectome will help us understand human identity. In his talk, Seung encourages his audience to say along with him. “I am my connectome.” He’s written a new book on this subject, Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are.

This is an ambitious research project that will no doubt yield highly improved techniques to get anatomical information and analyze it. We will learn a lot from it.

And it will fail.

The allure, promise, and shortcomings of the connectome approach are yesterday’s news to neuroethologists. In the 1960s and 1970s, neuroethologists put in a lot of effort to crack partial connectomes of several species. These were usually referred to as “circuits” or “wiring diagrams.” (“Connectome” only appeared when neuroscientists got genome envy.) We made good progress on these. For example, we can explain escape behaviour in fishes and crayfish by the main synaptic connection between the critical neurons. That said, escape systems were chosen specifically because they were unusual behaviours. they are very sterotyped, very fast, and dedicated to one single task.

As other circuits were cracked, they revealed a much more subtle story.

A new paper by Bargmann details the case histories of a few of the species that neuroethologists have basically cracked the circuit. And contrary to some expectations, getting the complete set of synaptic connections did not solve the problems of understanding behaviour. I’m very glad that Bargmann wrote this paper, because it saves me the trouble of writing a much longer blog post.

A new paper by Bargmann details the case histories of a few of the species that neuroethologists have basically cracked the circuit. And contrary to some expectations, getting the complete set of synaptic connections did not solve the problems of understanding behaviour. I’m very glad that Bargmann wrote this paper, because it saves me the trouble of writing a much longer blog post.

For example, the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans has 302 neurons, and all the connections between them are known (the first complete connectome in the animal kingdom). Bargmann writes:

One of the major lessons that emerged in the 1990s from the study of these small circuits where we knew all the synaptic connections was the importance of neuromodulation. Neurons’ functions were not set only by their anatomical connections. They were profoundly influenced by a cocktail of neuroactive chemicals that could change the physiological responses of neurons.

Bargmann breaks it down. First, she shows that only rarely can you link single neurons to single behaviours. Then, she shows how one behaviour can result from several circuits, and how one neuromodulator can influence several behaviours. She notes that given how neuromodulation has appeared pretty much in every nervous system where we’ve looked, there’s every reason to expect it’s going to be a major factor in determining human neural activity, and thus, human identity.

In his TED talk, Seung draw an extended metaphor that the connectome is like the bed of a river.

Knowing the bed of the river still doesn’t tell you everything. The same river bed can have a trickle one day, and a flash flood the next. Neuromodulation is a bit like a dam partway along the river. It can regulate whether you have a torrent or a trickle.

Bargmann and I agree that connectome projects are very useful. But they alone will not solve the question of human identity. But at least when they fail, they will fail in an interesting way.

Reference

Bargmann C. 2012. Beyond the connectome: How neuromodulators shape neural circuits. BioEssays: In press. DOI: 10.1002/bies.201100185

One of the major proponents of this effort has been Sebastian Seung, who you can see giving a TED talk here. He sells the idea that understanding the human connectome will help us understand human identity. In his talk, Seung encourages his audience to say along with him. “I am my connectome.” He’s written a new book on this subject, Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are.

One of the major proponents of this effort has been Sebastian Seung, who you can see giving a TED talk here. He sells the idea that understanding the human connectome will help us understand human identity. In his talk, Seung encourages his audience to say along with him. “I am my connectome.” He’s written a new book on this subject, Connectome: How the Brain’s Wiring Makes Us Who We Are.This is an ambitious research project that will no doubt yield highly improved techniques to get anatomical information and analyze it. We will learn a lot from it.

And it will fail.

The allure, promise, and shortcomings of the connectome approach are yesterday’s news to neuroethologists. In the 1960s and 1970s, neuroethologists put in a lot of effort to crack partial connectomes of several species. These were usually referred to as “circuits” or “wiring diagrams.” (“Connectome” only appeared when neuroscientists got genome envy.) We made good progress on these. For example, we can explain escape behaviour in fishes and crayfish by the main synaptic connection between the critical neurons. That said, escape systems were chosen specifically because they were unusual behaviours. they are very sterotyped, very fast, and dedicated to one single task.

As other circuits were cracked, they revealed a much more subtle story.

For example, the nematode worm Caenorhabditis elegans has 302 neurons, and all the connections between them are known (the first complete connectome in the animal kingdom). Bargmann writes:

At a more profound level, however, the wiring diagram was and remains difficult to read. The neurons are heavily connected with each other, perhaps even overconnected – it is possible to chart a path from virtually any neuron to any other neuron in three synapses. ... Circuit studies suggest a reason for this failure: there is no one way to read the wiring diagram.

One of the major lessons that emerged in the 1990s from the study of these small circuits where we knew all the synaptic connections was the importance of neuromodulation. Neurons’ functions were not set only by their anatomical connections. They were profoundly influenced by a cocktail of neuroactive chemicals that could change the physiological responses of neurons.

Bargmann breaks it down. First, she shows that only rarely can you link single neurons to single behaviours. Then, she shows how one behaviour can result from several circuits, and how one neuromodulator can influence several behaviours. She notes that given how neuromodulation has appeared pretty much in every nervous system where we’ve looked, there’s every reason to expect it’s going to be a major factor in determining human neural activity, and thus, human identity.

In his TED talk, Seung draw an extended metaphor that the connectome is like the bed of a river.

I would like to propose a metaphor for the relationship between neural activity and connectivity. Neural activity is constantly changing. It's like the water of the stream; it never sits still. The connections of the brain's neural network determines the pathways along which neural activity flows. And so the connectome is like bed of the stream; but the metaphor is richer than that, because it's true that the stream bed guides the flow of the water, but over long timescales, the water also reshapes the bed of the stream. And as I told you just now, neural activity can change the connectome. And if you'll allow me to ascend to metaphorical heights, I will remind you that neural activity is the physical basis – or so neuroscientists think – of thoughts, feelings and perceptions. And so we might even speak of the stream of consciousness. Neural activity is its water, and the connectome is its bed.

Knowing the bed of the river still doesn’t tell you everything. The same river bed can have a trickle one day, and a flash flood the next. Neuromodulation is a bit like a dam partway along the river. It can regulate whether you have a torrent or a trickle.

Bargmann and I agree that connectome projects are very useful. But they alone will not solve the question of human identity. But at least when they fail, they will fail in an interesting way.

Reference

Bargmann C. 2012. Beyond the connectome: How neuromodulators shape neural circuits. BioEssays: In press. DOI: 10.1002/bies.201100185

07 March 2012

Go Barsoom!

I am excited that Edgar Rice Burroughs’s John Carter of Mars is coming to the movie theatres*, just in time for its hundredth anniversary.

While the story has a lot of trappings that we’ve come to associate with high fantasy (swords, princesses, and the like), I want to make the case that A Princess of Mars is truly science fiction. And despite that it’s early science fiction, and that scientific knowledge has moved on in the last century, Burroughs got something right. Indeed, it’s something that later, ostensibly more sophisticated science fiction tends to gloss over, particularly in film and television.

Gravity.

Mars, Burroughs reminds us, has lighter gravity than Earth. Lower gravity means that John Carter, a Virginia everyman, becomes stronger than he ever would be on Earth. (Later, Superman’s would repeat the twist, with Krypton and Earth substituting for Earth and Mars.) The scientific fact about this basic force of nature is woven into the warp and weft of the books, and is never forgotten.

In contrast, gravity is ignored in most popular science fiction. People walk around on spaceships in the middle of interstellar travel as though they were on a building, not in weightlessness.

Occasionally, you’ll hear some one-liner tossed off about “artificial gravity generators” or some such to explain this. This is a good time to remember that of the four fundamental forces we know in this universe – gravity, the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force, and electromagnetism – we can only manipulate the last of those. Physicists are still betting on whether the Large Hadron Collider will finally reveal why things have mass.

I sympathize with filmmakers. Trying to simulate weightlessness is tricky, and requires complicates special effects. But I do wish that they would address it more often. And judging from the previews, I’m happy that the makers of John Carter have chosen to embrace this aspect of the story, and that it is given due credit as the science fiction pioneer that it is.

* This is despite Disney giving the film the most boring and nonevocative logo in memory. Akzidenz-Grotesk? This does not convey any of the familiarity of the turn of the Victoria era or the alien nature of the Martian landscape. And the title isn’t much better. Just John Carter? Not even John Carter of Mars?

Book cover from here, a great site that contains lots of information and artwork from many printings of the story. For me, Frank Frazetta’s interpretation of Barsoom is definitive.

While the story has a lot of trappings that we’ve come to associate with high fantasy (swords, princesses, and the like), I want to make the case that A Princess of Mars is truly science fiction. And despite that it’s early science fiction, and that scientific knowledge has moved on in the last century, Burroughs got something right. Indeed, it’s something that later, ostensibly more sophisticated science fiction tends to gloss over, particularly in film and television.

Gravity.

Mars, Burroughs reminds us, has lighter gravity than Earth. Lower gravity means that John Carter, a Virginia everyman, becomes stronger than he ever would be on Earth. (Later, Superman’s would repeat the twist, with Krypton and Earth substituting for Earth and Mars.) The scientific fact about this basic force of nature is woven into the warp and weft of the books, and is never forgotten.

In contrast, gravity is ignored in most popular science fiction. People walk around on spaceships in the middle of interstellar travel as though they were on a building, not in weightlessness.

Occasionally, you’ll hear some one-liner tossed off about “artificial gravity generators” or some such to explain this. This is a good time to remember that of the four fundamental forces we know in this universe – gravity, the strong nuclear force, and the weak nuclear force, and electromagnetism – we can only manipulate the last of those. Physicists are still betting on whether the Large Hadron Collider will finally reveal why things have mass.

I sympathize with filmmakers. Trying to simulate weightlessness is tricky, and requires complicates special effects. But I do wish that they would address it more often. And judging from the previews, I’m happy that the makers of John Carter have chosen to embrace this aspect of the story, and that it is given due credit as the science fiction pioneer that it is.

* This is despite Disney giving the film the most boring and nonevocative logo in memory. Akzidenz-Grotesk? This does not convey any of the familiarity of the turn of the Victoria era or the alien nature of the Martian landscape. And the title isn’t much better. Just John Carter? Not even John Carter of Mars?

Book cover from here, a great site that contains lots of information and artwork from many printings of the story. For me, Frank Frazetta’s interpretation of Barsoom is definitive.

06 March 2012

Carnivals for March 2012

The Carnival of Evolution #45 is up at Splendour Awaits. The first slideshow in this carnival’s history, I think!

Circus of the Spineless #70 is at Beasts in a Populous City.

Circus of the Spineless #70 is at Beasts in a Populous City.

Tuesday Crustie: I’m not yellow... I just have yellow tips

Have no idea of the species of this crab, photographed in waters around New Guinea. I just love the yellow accents.

Photo by bbialek905 on Flickr; used under a Creative Commons license.

05 March 2012

“Kids”

I get annoyed whenever I hear university instructors, either in person or online, referring to their students as “kids.”

It’s disparaging. It’s dismissive. It undervalues their abilities and undercuts their views.

University students are adults. They don’t deserve to be tagged as children any more.

(Exceptions will be made for any student who is a goat.)

It’s disparaging. It’s dismissive. It undervalues their abilities and undercuts their views.

University students are adults. They don’t deserve to be tagged as children any more.

(Exceptions will be made for any student who is a goat.)

The Zen of Presentations, Part 51: Redrawn

“This is so ugly.”

I have been preparing for my talk at the University of Texas San Antonio this week. For context and background, I wanted to include some graphs from other, previously published papers as well as my own stuff. There were two problems.

First, the quality of the graphs I wanted to use wasn’t always there. Many were old, pixelated images. Some graphs had unlabelled error bars, and some had text overlapping with error bars. Some bar graphs had hatching to distinguish the bars that was not very pleasing to look at.

Second, the style of the images I wanted to use varied wildly. Some were monochrome, some used colour. Some used serif types, some used sans serif type. The shape of the graphs sometimes didn’t come anywhere near the shape of the slide.

Even with my own material, I was pulling together images from several years and projects – manuscripts, conference posters, unpublished stuff – and I was painfully aware that it didn’t fit together very well. As I’ve written about before, consistency matters.

So I redrew everything.

With my own material, this was tedious but straightforward. I just had to locate a lot of archived files on my hard drive, opened them up, and started changing fonts, colours, and proportions.

Making other people’s stuff consistent can be trickier. First, I typically had to grab images. For PDF files, there is a snapshot tool in Adobe Reader that lets you do grabs of anything on the screen. It isn’t turned on in the toolbar by default, though. Click at right to enlarge.

Making other people’s stuff consistent can be trickier. First, I typically had to grab images. For PDF files, there is a snapshot tool in Adobe Reader that lets you do grabs of anything on the screen. It isn’t turned on in the toolbar by default, though. Click at right to enlarge.

Once I have a grab of the graphic, I can then put it into a full graphics editor (I’m a Corel Photo-Paint user myself; other software packages are available). For instance, I can get rid of text that I don’t need or remove the background. But even PowerPoint can do some basic manipulations quite well.

For some graphs, I need to go right back to ground zero and redraw the graph in my own software. There is a shareware program called Datathief that I’ve used to get extract information from published graphs so I can replot it. It’s fairly simple to use for distinct data points, like scatter plots or bar charts. I haven’t tried to extract a curve yet.

For some graphs, I need to go right back to ground zero and redraw the graph in my own software. There is a shareware program called Datathief that I’ve used to get extract information from published graphs so I can replot it. It’s fairly simple to use for distinct data points, like scatter plots or bar charts. I haven’t tried to extract a curve yet.

I have heard that data extraction from published graphs is possible in Matlab, though I haven’t done it myself.

In the end, almost every image in my presentation has been altered, tweaked, cropped, redrawn, recoloured, resized, or revised. It took a few solid days to do it. I am convinced it’s worth it, though. The level of harmony in the talk is so much higher, and the overall effect of the presentation is so much stronger, than if I had just left it looking like a scrappy quilt.

Related posts

The Zen of Presentations, Part 41: Consistency

I have been preparing for my talk at the University of Texas San Antonio this week. For context and background, I wanted to include some graphs from other, previously published papers as well as my own stuff. There were two problems.

First, the quality of the graphs I wanted to use wasn’t always there. Many were old, pixelated images. Some graphs had unlabelled error bars, and some had text overlapping with error bars. Some bar graphs had hatching to distinguish the bars that was not very pleasing to look at.