Lots of academics are upset by bad journals, which are often labelled “predatory.” This is maybe not a great name for them, because it implies people publishing in them are unwilling victims, and we know that a lot are not.

Lots of scientists want guidance about which journals are credible and which are not. And for the last few years, there’s been a lot of interests in lists of journals. Blacklists spell out all the bad journals, whitelists give all the good ones.

The desire for lists might seem strange if you’re looking at the

problem from the point of view of an author. You know what journals you

read, what journals your colleagues publish in, and so on. But part of

the desire for lists comes when you have to evaluate journals as part of

looking at someone else’s work, like when you’re on a tenure and

promotion committee.

But a new paper shows it ain’t that simple.

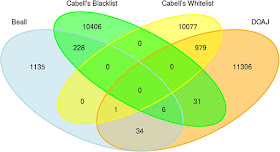

Strinzel and colleagues compared two blacklists and two whitelists, and found some journals appeared on both the lists.

There are some obvious problems with this analysis. “Beall” is Jeffrey Beall’s blacklist, which he no longer maintains, so it is out of date. Beall’s list was also the opinion of just one person. (It’s indicative of the demand for simple lists that one put out by a single person, with little transparency, could gain so much credibility.)

One blacklist and one whitelist are from the same commercial source (Cabell), so they are not independent samples. It would be surprising if the same sources listed a journal on both its whitelist and blacklist!

The paper includes a Venn diagram for publishers, too, which shows similar results (though there is a published on both Cabell’s lists).

This is kind of like I expected. And really, this should be yesterday’s news. Let’s remember the journal Homeopathy is put out by an established, recognized academic publisher (Elsevier), indexed in Web of Science, and indexed PubMed. It’s a bad journal on a nonexistent topic that was somehow “whitelisted” by multiple services that claimed to be vetting what they index.

Academic publishing is a complex field. We should not expect all journals to fall cleanly into two easily recognizable categories of “Good guys” and “Bad guys” – no matter how much we would like it to be that easy.

It’s always surprising to me that academics, who will nuance themselves into oblivion on their own research, so badly want “If / then” binary solutions to publishing and career advancement.

If you’re going to have blacklists and whitelists, you should have graylists, too. There are going to be journals that have some problematic practices but that are put out by people with no ill intent (unlike “predatory” journals which deliberately misrepresent themselves).

Reference

M Strinzel, Severin A, Milzow K, Egger M. 2019. Blacklists and whitelists to tackle predatory publishing: A cross-sectional comparison and thematic analysis. mBio 10(3): e00411-00419. https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00411-19.

Related posts

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are moderated. Real names and pseudonyms are welcome. Anonymous comments are not and will be removed.