“Progress” and “evolution” are inextricably linked in many people’s minds. Evolution is always moving forward. From molecules to cells to invertebrates to vertebrates; from fish to reptiles to mammals to us. There’s a lot wrong with those ideas, but the underlying question is worth asking: Can organisms go back the way they came?

Louis Dollo thought not. He suggested that once a feature was lost in a lineage, it could never be regained. Enough people agreed with this suggestion that it became known as “

Dollo’s Law.” A couple of recent papers address whether Dollo’s suggestion was a correct one.

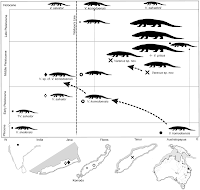

The first paper, by Lynch and Wagner, tests Dollo’s Law at the organismal level. It follows previous suggestions that reptiles have flip-flopping between egg-bearing and live birth. These were only suggestive, because scenarios with

no reversals were just about as likely as those without.

The boa family

Boidae may provide a strong test of whether evolutionary zig-zagging occurred with egg-bearing. Boas generally give birth to live young, but two do

not.

It is possible that these egg-layers were the earliest species to branch off from the rest of the family, which then evolved live-birth, but if so, there should be a raft of other features marking them as very divergent from all other boas.

As is typical now, most of the features examined are DNA. Much of this paper details relationships between many genera of boas, with the specific question about egg-laying being a rather small cookie in what is obviously a much bigger systematic meal. Disappointingly, one of the two-egg-laying boas,

Eyrx muelleri (pictured), is not included in this analysis.

The genus

Eryx is not an early branch within the boa family, however. The one egg-laying species examined here,

Eryx jayakari, is nestled firmly in the middle of the boa family tree, which strongly indicates that its ancestors were live-bearing boas.

Showing

that reversals happened does not answer

why or

how they happened. Lynch and Wagner do discuss some of the selective pressures that may have led to these particular species re-evolving egg-laying. Both live in desert environments, which could be a key factor in what led to the loss of live birth.

A major question for understanding reversals is just how similar the re-evolved feature is to the original. To qualify as a true reversal, the similarities would have to be very extensive and detailed. Otherwise, this may not be a case of reversal, but of convergence instead. The authors note that other snakes have a small tooth to push through the eggs when hatching, but hatchlings in these two boa species do

not, indicating that the boas have not wound the clock back entirely or exactly.

Understanding whether this is reversal rather than convergence will probably require doing detailed anatomy of the reproductive organs of a lot of snakes. DNA is great for understanding the relationships between species, but it will probably only be by looking closely at the actual organisms that we will be able to understand the chain of events that might lead groups back the way they came.

A second paper, by Bridgham and collegues, argues that at the level of molecules, Dollo may have been on the money. They ran models of the evolution of a molecular that binds to the hormone cortisol. According to their model, the cortisol receptor was derived from receptors that bound to a much wider range of molecules. The new receptor, then, is a specialization of generalists.

When they took the modern receptor, and experimentally changed several key mutations back to the predicted ancestral state, they got a molecule that bound to... nothing. Bridgham and company’s explanation is that in addition to the key mutations that made the modern receptor possible, there were other changes in the rest of the molecule that. These “background” changes were not obviously related to the molecule’s ability to bind to the hormone, but, in the context of a long, complex molecule where the parts interact to give the receptor it shape, those changes were enough to prevent the experimentally modified receptor to bind to hormones.

Interestingly, the authors stress that these background changes make it unlikely for the molecule to revert back to its ancestral condition... but then they proceed to

do it (their Figure 3a). Sure, the chain of events needed to revert the molecule back is longer and less probable. The ratchet they propose for molecular evolution may be a slightly slippery one.

In a sense, both papers show that the argument about evolutionary reversal is not whether it is possible or impossible. The question is not whether reversals happen, but how often they happen. Reversals could be rare. And the frequency of reversal may differ depending on what level of organization you’re looking at. It could be easier in whole organisms than in molecules, or

vice versa.

This post is part of National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCENT) competition for the Science Online 2010 conference.ReferencesBridgham, J., Ortlund, E., & Thornton, J. (2009). An epistatic ratchet constrains the direction of glucocorticoid receptor evolution Nature, 461 (7263), 515-519 DOI: 10.1038/nature08249Lynch, V., & Wagner, G. (2009). Did egg-laying boas break Dollo's Law? Phylogenetic evidence for reversal to oviparity in sand boas (Eryx: Boidae) Evolution DOI: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00790.x

This post is part of National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCENT) competition for the Science Online 2010 conference.ReferencesBridgham, J., Ortlund, E., & Thornton, J. (2009). An epistatic ratchet constrains the direction of glucocorticoid receptor evolution Nature, 461 (7263), 515-519 DOI: 10.1038/nature08249Lynch, V., & Wagner, G. (2009). Did egg-laying boas break Dollo's Law? Phylogenetic evidence for reversal to oviparity in sand boas (Eryx: Boidae) Evolution DOI: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2009.00790.xPicture from

here.