As I talked about in an earlier post, weird things happen to the size of species on islands. Big species get small. Small species get big.

And if there’s one thing that people know about Komodo dragons, it’s that they’re big. It wouldn’t surprise me if Komodo dragons feature on a Trivial Pursuit card somewhere: “What is the largest lizard in the world?” They are the biggest, which means they’re the sort of animal that most people know about, so interested are we with extremes, particularly large extremes. Yet despite this, Komodo dragons were featured on the cover of Last Chance to See by Douglas Adams and Mark Carwadine as an endangered species.

And if there’s one thing that people know about Komodo dragons, it’s that they’re big. It wouldn’t surprise me if Komodo dragons feature on a Trivial Pursuit card somewhere: “What is the largest lizard in the world?” They are the biggest, which means they’re the sort of animal that most people know about, so interested are we with extremes, particularly large extremes. Yet despite this, Komodo dragons were featured on the cover of Last Chance to See by Douglas Adams and Mark Carwadine as an endangered species.Are all these things – living on islands, the large size, the small range the animals occupy – all connected somehow? That is, did Komodo dragons start out as Komodo wyverns (small dragons) and evolve large size because they were on these small islands? Alternately, did Komodo dragons evolve from “Widely distributed South Pacific” dragons, meaning they were just big from the start?

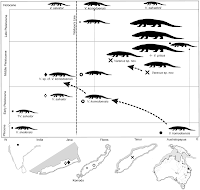

A new paper by Hucknall and colleagues tries to tease out these possibilities, and suggests that the Komodo dragons’ island home isn’t all that related to their size.

Hucknall and company get to say, “We have the fossils. We win.”

Somewhat to my surprise, Komodo dragons have a fossil record that goes back a good long while. The authors here have fossil going back almost a million years, in fact. Most of this paper is classic comparative vertebrate anatomy; lots of notes of condyles and grooves and the like.

These Kododo dragon fossils are found not just on smallish islands where the species lives now... but on mainland Australia. And the ones in Australia are actually the oldest fossils. Because these fossils are recognizable as the same species, and the fossil timeline starts on the mainland and continues to the islands, the evidence does not support a scenario where the ancestors of the Komodos were little dwarfs that got bigger once they reached the islands.

This paper goes on to analyze several other fossil species, including one unnamed new species. They are all big. Interestingly, one old lineage occurs on mainland Asia, quite some distance from Australia, indicating that this particular line of very large lizards was very widespread across the Old World. This particular paper doesn’t address where the group might have originated form in the first place.

This paper goes on to analyze several other fossil species, including one unnamed new species. They are all big. Interestingly, one old lineage occurs on mainland Asia, quite some distance from Australia, indicating that this particular line of very large lizards was very widespread across the Old World. This particular paper doesn’t address where the group might have originated form in the first place.The sad news is that the range, population, and number of species of these lizards are all ghosts of their former selves. We value these animals enough that they will probably be kept in zoos indefinitely, but it would be a shame if that became the only place they lived.

Reference

Hocknull, S., Piper, P., van den Bergh, G., Due, R., Morwood, M., & Kurniawan, I. (2009). Dragon's Paradise Lost: Palaeobiogeography, Evolution and Extinction of the Largest-Ever Terrestrial Lizards (Varanidae) PLoS ONE, 4 (9) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007241

No comments:

Post a Comment