Stories I've been meaning to point to or comment on...

In the Austin American-Statesman last month,

an opinion piece by two educational faculty from Baylor argued that biologists should not set the science curriculum for Texas. They argue, first, that religions of various sorts should be taught and studied in curriculum.

What (scientists) probably reject is the inclusion of discussions about religion in biology texts and classes. As that biologist claimed, "We shouldn't be teaching the supernatural in science classrooms." Setting aside the false assertion that religion is nothing but the "supernatural," biologists still, however, have not established a persuasive educational argument as to why religion should be banned from discussions of science.

Glanzer and Null do not explain what they think defines a religion aside from the supernatural. While there is more to religions that the supernatural, few to no religions have

no supernatural elements. Regardless, it's those supernatural elements that generate the conflicts with established science.

It's very difficult to glean what Glanzer and Null have in mind here for including religions in science, particularly at the K-12 level. Do they want teachers to mention that Charles Darwin loved William Paley's

Natural Theology? Do they think it is legitimate to teach, in a K-12 science class, that the Earth is about 6,000 years old, and fossils were generated by the Biblical flood of Noah? Because that would be

illegal, not to mention unsupported by science.

One major reason why religious views should not be included in science classes is that such views are irrelevant, scientifically speaking. They make no testable hypotheses, generate no predictions, except for the few that have been tested, found wanting, and rejected because they did not explain the evidence.

Many questions remain unanswered by the biologists who seem most interested in trying to control curriculum. Why do biologists assume they are experts in curriculum when they are not? Why are biologists afraid to broach the exciting intellectual problems surrounding the relationship between faith and science? Why not discuss the history of biology as a discipline and how the field's approach to this problem has evolved over time? Why not discuss with students why biologists tend to operate within a naturalistic framework, including the benefits and limitations of the framework?

To answer their rhetorical questions in order:

At the university level, biologists

do set the curriculum, and are the experts in curriculum at that level. That is the only domain for which expertise is claimed, and it is appropriate for us to do so. Because one of the goals of K-12 education is to prepare students for university, there should be alignment of the two. There is little point to teaching material that will not help students who go on to university.

Biologists are not afraid of exciting intellectual problems between faith and science, but such problems are pretty damn thin on the ground. We're not talking about subtle philosophies of free will and predestination here -- we're talking about strong, simple claims that are not supported by science. The Earth is

not a few thousand years old. There

are transitional fossils. Organisms

have changed over millions of years. Bringing in religious claims to the contrary isn't an exciting intellectual problem, it's a rehash of discredited claims that are old and tedious and bloody boring.

We do.

We do. Although I wonder what "limitations" they're referring to.

Moving on,

this story from the start of last month mentions how signatories of the 21st Century Science Coalition includes several who teach as Christian institutions. You can tell the story is out of date, since

the number of signatures is now pushing 1400, not 800.

A short piece by TV station KFDA notes:

Even if the strengths and weaknesses phrase is deleted, Buchanan says that will not stifle a student's question on evolution.

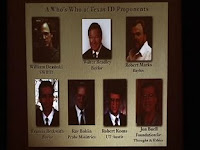

Barbara Forest has a talk recorded at Southern Methodist University on 11 November 2008, specifically about Texas.

Barbara Forest has a talk recorded at Southern Methodist University on 11 November 2008, specifically about Texas.