22 May 2018

Tuesday Crustie: Mollie

Yes, those are light sabers. Slate has the story behind this adorable creation.

Hat tip to Miriam Goldstein.

18 May 2018

All scholarship is hard

Nicholas Evans wrote:

Nicholas Evans wrote:The solution levied by synthetic biologists is to get more biologists doing ethics. That this is always the suggestion tells me a) you think it’s easier to think about ethics than synbio; b) you want to keep the analysis in house. Neither are good.

Seconded, confirmed, and oh my God yes. I’ve been through several iterations of this in biology curriculum meetings, where I or others have suggested incorporating some non-biology class into a degree program, or even just an elective students funded by a training grant have to take. And the reaction is just what Nicholas describes:

“Why don’t we just do it ourselves?”

The single exception seemed to be chemistry. Maybe there was less suspicion because of the blurry line between molecular biology and biochemistry. Or maybe it was because their department was right above ours and we knew the people better. But when it was ethics or writing or statistics: nope, we’ll develop out own class taught by our own faculty in our own department.

I get a lot of variations of “Is is easier to do this or that in academia?” questions on Quora, too.

In an institution, this attitude of “We know best” is made worse by administrative measurements. Departments are evaluated by how many credit hours they generate. So when I suggest students might take a course taught by the Philosophy or Math or Communications or Psychology department, the response is, “We’re just giving credit hours away.” Since credit hours are one thing that are looked at to determine resources, it’s an understandable reaction. It’s Goodheart’s law in action. The measure becomes a target and changes what the measure does.

Nicholas notes:

The vast majority of people talking synbio ethics have almost no training in ethics. You wouldn’t accept that in the technical side of synbio, so don’t accept it in ethics.

Exactly. We often complain about how people don’t respect expertise on many controversial subjects, like evolution, climate change, or vaccination. But we see the same disrespect within universities for scholarship in different fields. Scholarship in every field is hard, and “My field is better than your field” is a shitty game.

Hat tip to Janet Stemwedel.

16 May 2018

The Zen of Presentations, Part 71: Slides per minute

In grad school, I was introduced to a nice, simple rule for giving a talk.

One slide per minute.

I used this rule for a long time. It seemed to work well. In particular, any slide with data seemed to take at least a minute to digest. You had to orient yourself to the axis labels, the units, there is reader an interpretation to do, and that takes a little time.

I did know it was a rule of thumb, not an ironclad rule. I would estimate a slide would be up for a little less than a minute when it was a picture of an animal or something else that had no data or nothing to read.

But then I saw Lawrence Lessig’s presentation, “Free culture” (via Garr Reynolds’s blog). His talk had 243 slides, but it was not 243 minutes. Lessig used his slides in a way I’d never seen before. They weren’t illustrations to be described or explained. His slides were his rhythm section, laying out a beat and emphasizing what he said. Even though his slides were up for such a short time, I never felt confused or lost or thinking, “Wait, wait, go back!”

I was blown away. I showed me how limited my views about what a “good presentation” were.

Then I learned about formats like pecha kucha and Ignite talks. Like Lessig, they emphasized quick pacing, running through slides at 3 to 4 per minutes. And those talks often rocked.

The key to such rapid fire delivery was planning and practice. The automatic slide advance rule for pecha kucha and Ignite talks forced to you plan and practice relentlessly. Practice never leads you wrong.

There are some images and slides that probably do warrant a full minute. But the audience can often pick up on points faster than you’d think.

There isn’t any magic number of slides in a talk. Your talk can have hundreds of slides. Your talk can have no slides. Or your talk can even have one slide per minute.

Update, 3 December 2021: Lawrence Lessig’s free culture talk was originally presented as a Flash animation, which is mostly dead now.

Here it is, in parts, on YouTube: Part 1 • Part 2 • Part 3.

Related posts

External links

Free culture presentation

The “Lessig method” of presentation

11 May 2018

The Zen of Presentations, Part 70: Giving away the plot

Huge mistake to design scientific presentation like fucken Sherlock Holmes story.

Becca replied:

If you set things up and present your logic at every step, the audience can tell where things are headed without being explicitly told in advance.

Over on Better Posters, I’ve talked a lot about the Columbo principle. Columbo taught us that even when the audience knows the answer, the fun can be in learning how you prove it. I think that advice works well for titles, but it still implies a sort of “mystery” aspect that Nitenbach is criticizing.

But you can structure a talk where you tell the audience what’s going to happen, but not leave them disappointed.

When making Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, writer Nicholas Meyer (who also directed) was faced with a problem: Spock, the show’s most popular character, was going to die.

Actor Leonard Nimoy was bored with the part, not interested in doing another movie, and was sort of lured back in by the prospect of killing off the character. Fans learned about this, and were upset. Meyer got death threats. So what did Meyer do?

He killed Spock in the opening scene.

Of course, Spock doesn’t actually die at that point. He pretends to die as part of the Kobayushi Maru training scenario. So when the film is winding up for the actual, powerful death scene of Spock, people were not thinking about, “This is the one where Spock dies!”

Meyer said he learned on this movie that you can show an audience anything in the first ten minutes of a movie, and they will forget about it by the end of the movie.

You can do the same thing in a talk. You can tell people right at the start of a talk what you found. If you involve them, and make the narrative of that process well told, you can bring people through to the end, and they will think, “Oh yeah, I already knew that!”

Meyer said in the film’s Blu-ray commentary:

The question is not whether you kill him. It’s whether you kill him well. If it’s perceived as a working out of a clause in a star’s contract, then they’re gonna hate it. If it’s organic, if it’s really part of the story, then no one’s gonna object.

Or, to paraphrase Anton Chekov, if you want fire a gun in the third act, load it in the first act. The audience will forget the gun was even loaded until that final climactic shot.

External links

Detective stories: “Whodunnit?” versus “How’s he gonna prove it?”

38 Things We Learned from the ‘Star Trek II’ Commentary

04 May 2018

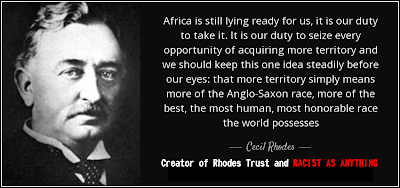

Rhodes Trust is academia’s equivalent to Confederate statues and flags

In the last few years in the United States, there’s been debate about the presence of Confederate flags and statues in public places. I credit Bree Newsome for getting this ball rolling. The Confederacy was built on the notion that slavery was right and just.

Continuing to display the symbols of that failed government on public grounds is tacit endorsement of the ideals of white supremacy. Put those statues and flags that are on government property in museums.

This morning, I was given a link to a fellowship and was asked to promote it. I had two problems with that, and the first was that the fellowship had a lot of ties to the Rhodes Trust.

As a student, I learned about Cecil Rhodes because of his association with Oxford’s Rhodes Scholarships (supported by the Rhodes Trust). That name had a positive association for me.

It was only later that I learned, “Man, this dude was racist as fuck.” In Born a Crime, Trevor Noah says if many Africans had a time machine, they wouldn’t go back in time to stop Adolf Hitler, they’d be packing heat for Cecil Rhodes. (Edit: Yes, this is admittedly a big gap in my education. I should have known.)

I wish I had learned about Rhodes’s colonial racism first, not years after hearing about the scholarships. The misery Rhodes caused in life seems more important to me than the money he left behind after death.

The second problem I had with this fellowship was that it was for “leading academic institutions.” I’m pretty sure that means American Ivy League institutions and English Oxbridge universities, and not the sort of public, regional institutions where most students in the world get their university educations. (The sort of place I work.)

Racist and elitist was not a winning combination for me. I did not push out notification of the fellowship. Admittedly, this was made easier because the deadline was past, but I wouldn’t have done it regardless.

Is Rhodes the only example? When I mentioned this on Twitter, “Sackler” came up. Like Rhodes, I first heard that name in a positive light: the Sackler symposium on science communication, which I’ve blogged about several times (here in 2012, here in 2013). But the Sackler family is problematic: they made a lot of money from opioids, which is now a major public health problem. And that name is on museums and medical schools.

Like Rhodes, I should have known about the Sackler drug connection before I knew about the symposium. That’s not good.

Turning money isn’t as easy as taking down a flag on a pole, or a statue in a park. But the principle is the same. Academia needs to look harder at how to stop giving these unspoken endorsements to people who caused a lot of suffering.

Update, 14 May 2018: Poll results from Twitter. 88% of people surveyed said they’d take money with the Rhodes name.

Picture from here.

Rethinking the graduate admissions process

The process for selecting graduate students is mostly deeply flawed and should be revamped from the ground up. Almost everything in the admission process works against increasing diversity in academia.

The process for selecting graduate students is mostly deeply flawed and should be revamped from the ground up. Almost everything in the admission process works against increasing diversity in academia.Let’s take the elements apart piece by piece.

Application fee: Many program charge an application fee. This works against students who are good, but economically disadvantaged. There is no way that those fees are paying the bills of the graduate office, Friction can be a useful thing in preventing spurious applications, but generally the cost is so high that multiple applications quickly add up and remove options from students who can’t pay them all.

GRE scores: The cost of writing and submitting scores is another economic barrier. Many have written about the low predictive power of the test (also here).

Undergraduate GPA: Grade inflation is making it difficult to distinguish student performance. Plus, they are not exactly comparable from institution to institution, both in calculation (is the top score 4 or 4.3?), a situation that gets even more complex when student cross national borders. And it’s highly likely that the same grade point average will be interpreted differently depending on the issuing institution.

Recommendation letters: So much room for bias here. People write different recommendations for men and women. Like, twice the men get glowing letters than women. People are influenced by university of the letter writer and the seniority of the recommender and probably other factors that have nothing to do with the candidate. Recommendation letters are the primary tool for old boy’s networks to reinforce themselves.

CVs: Recently, we learned that a large number of graduate fellowship applicants were told they didn’t get the award because they didn’t have a publication yet. These are supposed to be people at the start of their academic careers, so it is not reasonable to expect them to have a lot on a CV. And given that so many places have not cracked down on unpaid internships, experience on paper will tend to favour people in well off families. Again.

Personal statement: This one might be okay, as long as applicants gave no indication of their gender. Because just the name alone works against increasing diversity.

If grad review is so messed up, what can we do?

One idea is to stop the tedious review by committee and just let individual faculty pick students they want to supervise. It doesn’t eliminate all the biases, but at least it’s less work.

In research grant applications, there’s occasionally serious suggestions crop up that the peer review process is kind of ineffective and that we’d be better off assigning funding by lottery. Maybe we should consider admitting grad students by lottery, too.

On Twitter, I asked students what they would like to see in the application process. Zachary Eldredge brings up the idea of a lottery, and Olivia mentions a face-to-face interview. Will Lykins says it would be good to normalize non-academic work on the forms, which again many students increasingly have to do to make ends meet instead of doing those unpaid enrichment activities.

Related posts

I come to bury the GRE, not to praise it

How do you test persistance?

Why grade inflation is good for the GRE

Does grad school have a mismatch problem?

The “Texas transcript” is a good idea, but won’t solve grade inflation