Ton van Raan had a paper rejected for referring to “sleeping beauty.” This is a term that van Raan and others have used to describe papers that aren’t cited for a long time and then start accumulated citations years after publication.

Rejection always makes academics grumpy, and van Raan is grumpy about this, unleashing the “political correctness gone mad” trope in his defense.

I went through something similar myself. I know first hand how easy it is to get defensive about deploying a common metaphor. But after you calm down and think about it, there is often a fair point to the criticism.

I think the editor had a good criticism but a bad implementation. Sleeping Beauty is problematic. Like many fairy tales, modern North Americans tend to know only very sanitized versions of the story. But even in the “clean” version, the part everyone remembers is pretty creepy.

I think the editor was right to ask for the author to not use Sleeping Beauty as a metaphor for scientific papers. Maybe a passing comment that this is how they have been referred to in the literature would be fine.

The editor may have failed in two ways.

The first was in rejecting the paper for a bad metaphor alone. If the scientific content was correct, it would seem that “Revise and resubmit” might have been a more appropriate response. It seems churlish to chuck the paper entirely for a poor metaphor, particularly one that is, for better or worse, already used by others in the literature.

The second was not offering a positive alternative to the Sleeping Beauty reference. Maybe these papers could be “buried treasures” or something that might be less problematic. There are many ways to express ideas. And neither an editor nor an author should dig in their heels over any particular way of expressing an idea.

Both of these problems assume the account offered by van Raan is accurate. Maybe there were other reasons for rejecting the paper besides the fairy tale reference. We don’t know.

Criticism can be valuable. Criticism plus suggestions for corrections are even better.

Hat tip to Marc Abrahams.

Related posts

Wake up calls for scientific papers

External links

Dutch professor astonished: comparison with Sleeping Beauty leads to refusal of publication

25 April 2019

Scientists’ unguarded moments

Earlier on Twitter, I shared an Instagram picture of Dr. Katie Bouman at work, imaging a black hole.

This has been a widely shared picture, and I was a little surprised when I saw a friend on Facebook question it. She said when there was scientific discoveries that showed images of men, the men looked more composed and professional. This made the imaging of a black hole look like an almost accidental “Did I do that?” moment.

Certainly Bouman’s picture was not the only one available. Here’s a picture of another one of the black hold team, Kazunori Akiyama.

Both Akiyama and Bouman are at computers, looking at the historic images they made. But Akiyama’s is almost certainly a staged, posed picture.

I asked what she thought of this picture of the New Horizons team, looking at images of Pluto close up for the first time. The man in the middle is project leader Alan Stern.

She replied that she thought it did a disservice to the science and to Stern if it had been widely reported. It had been seen quite widely, though probably not as much as the Bouman picture.

This interested me, because it spoke to the risks and rewards of scientists showing their unguarded moments.

On the one hand, these spontaneous moments capture something that is, I think, deeply human. Excitement. Joy. Achievement. Surprise.

But I also get that these are moments where people look undignified or vulnerable. It’s easy to mock people for looking goofy. Especially for big projects that have a lot of taxpayer money behind them, it might not be a good look. It can look like people just screwing around.

Personally, I think that sharing those spontaneous moments are worth it. My wife has been watching a lot of Brené Brown talks recently, and she talks a lot about the concept of vulnerability. And how vulnerability is one of the best predictors of courage.

I think scientists could use a lot more encouragement. And if that means looking in a way that surprises people, that’s all right by me.

Since I’m talking black holes, there was some discussion over who did what. Bouman got a lot of media attention, Sara Issaon pointed out that the image was not Bouman’s algorithms alone. Weirdly, this snowballed into some trying to undermine her contribution entirely. Andrew Chael ably tackled the trolls.

References

First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. IV. Imaging the Central Supermassive Black Hole

External links

Meet one of the first scientists to see the historic black hole image

This has been a widely shared picture, and I was a little surprised when I saw a friend on Facebook question it. She said when there was scientific discoveries that showed images of men, the men looked more composed and professional. This made the imaging of a black hole look like an almost accidental “Did I do that?” moment.

Certainly Bouman’s picture was not the only one available. Here’s a picture of another one of the black hold team, Kazunori Akiyama.

Both Akiyama and Bouman are at computers, looking at the historic images they made. But Akiyama’s is almost certainly a staged, posed picture.

I asked what she thought of this picture of the New Horizons team, looking at images of Pluto close up for the first time. The man in the middle is project leader Alan Stern.

She replied that she thought it did a disservice to the science and to Stern if it had been widely reported. It had been seen quite widely, though probably not as much as the Bouman picture.

This interested me, because it spoke to the risks and rewards of scientists showing their unguarded moments.

On the one hand, these spontaneous moments capture something that is, I think, deeply human. Excitement. Joy. Achievement. Surprise.

But I also get that these are moments where people look undignified or vulnerable. It’s easy to mock people for looking goofy. Especially for big projects that have a lot of taxpayer money behind them, it might not be a good look. It can look like people just screwing around.

Personally, I think that sharing those spontaneous moments are worth it. My wife has been watching a lot of Brené Brown talks recently, and she talks a lot about the concept of vulnerability. And how vulnerability is one of the best predictors of courage.

I think scientists could use a lot more encouragement. And if that means looking in a way that surprises people, that’s all right by me.

Since I’m talking black holes, there was some discussion over who did what. Bouman got a lot of media attention, Sara Issaon pointed out that the image was not Bouman’s algorithms alone. Weirdly, this snowballed into some trying to undermine her contribution entirely. Andrew Chael ably tackled the trolls.

References

First M87 Event Horizon Telescope Results. IV. Imaging the Central Supermassive Black Hole

External links

Meet one of the first scientists to see the historic black hole image

12 April 2019

“Open access” is not synonymous with “author pays”

Wingfield and Millar have a well-meaning but misleading article, “The open access research model is hurting academics in poorer countries.” They say:

The first sentence is correct. The second is even correct. It is true that there are now more journals that require article processing charges than their used to be. Importantly, though, the phenomenon of authors paying is not new. “Pages charges” existed long before open access.

But they lose all nuance in the third sentence and commit a category error. They are confusing “freedom to read” with “business model.” These two things are not the same.

There are many counter examples to their central premise. SciELO journals are open access, but have no article processing fees. I could go on.

I am not saying that there is not a concern about the effects of article processing charges. It isn’t even restricted to scientists in “poorer countries.” Michael Hendricks, a biologist at one of Canada’s major research universities (hardly a “poorer country” by any measure, and not even a “poorer institution” by any measure) is concerned about the cost of article processing charges. He wrote:

But looking back up to the counter-example, SciELO, shows something important. It shows that you can create open access journals with alternative business models that are not “author pays.” It’s unusual, maybe even difficult, but it’s not impossible.

That’s a line we should be pursuing. Not dumping on open access because people can’t distinguish between “common” and “necessary.”

External links

The open access research model is hurting academics in poorer countries

The open access model merely changes who pays. So rather than individuals or institutions paying to have access to publications, increasingly, academics are expected to pay for publishing their research in these “open access” journals. ... The bottom line is that payment has been transferred from institutions and individuals paying to have access to researchers having to pay to have their work published.

The first sentence is correct. The second is even correct. It is true that there are now more journals that require article processing charges than their used to be. Importantly, though, the phenomenon of authors paying is not new. “Pages charges” existed long before open access.

But they lose all nuance in the third sentence and commit a category error. They are confusing “freedom to read” with “business model.” These two things are not the same.

There are many counter examples to their central premise. SciELO journals are open access, but have no article processing fees. I could go on.

I am not saying that there is not a concern about the effects of article processing charges. It isn’t even restricted to scientists in “poorer countries.” Michael Hendricks, a biologist at one of Canada’s major research universities (hardly a “poorer country” by any measure, and not even a “poorer institution” by any measure) is concerned about the cost of article processing charges. He wrote:

US$2500 is 1% of an R01 modular budget. It is 2.5% of the average CIHR Project grant. It’s 10% of the average NSERC grant.

Add to that the vastly differing support across universities for article processing charges (ours is $0). There is no way around that fact that shifting publication costs from libraries to PIs imposes a massively different burden according to PI, field of science, nation, and institution.

The solution is that universities should pay article processing charges by cancelling subscriptions (with huge $ savings). But they generally aren’t. The only way I see to force the issue is for funders to make article processing charges ineligible, which will be seen as an attack on open access.

It’s real problem: library subscription costs are staying the same or going up. At the same time, more and more grant money is being spent on article processing charges. The public paying even more for science dissemination than they were is not what we want. Funders and/or universities have to stop this.

But looking back up to the counter-example, SciELO, shows something important. It shows that you can create open access journals with alternative business models that are not “author pays.” It’s unusual, maybe even difficult, but it’s not impossible.

That’s a line we should be pursuing. Not dumping on open access because people can’t distinguish between “common” and “necessary.”

External links

The open access research model is hurting academics in poorer countries

03 April 2019

Recommendation algorithms are the biggest problem in science communication today

Having been interested in science communication (and being a low-level practitioner) for a while, I recognized that there are a lot of old problems that recycle themselves. Like, “Should we have scientists or journalists communicating science to the public?” (Why not both?) “Is there value in debunking bad science, or does it make people dig in and turn off?” “Why can’t people name a living scientist?” “You have to tell a story...”

Having followed social controversies about science (particularly the efforts of creationists to discredit evolution) for a long time, I was almost getting bored seeing the same issues go ‘round and ‘round. But now I think we are truly facing something new.

Recommendation algorithms on social media.

You know these. These are the lines of computer code that tells you what books you might like on Amazon based on what you’ve bought in the past. It’s the way Facebook and Instagram deliver ads that you kind of like seeing in your feed. And it’s how Netflix and YouTube shows you want you might want to watch next.

I think recommendation algorithms may be the number one problem facing science communication today.

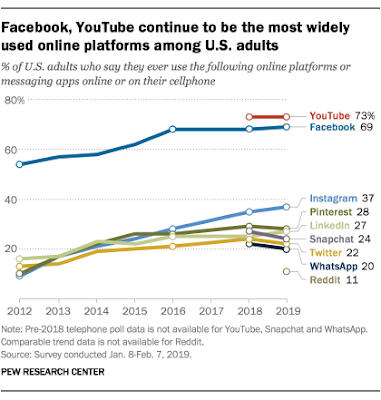

And of these, YouTube seems to be particularly bad. How bad is YouTube? Pretty bad, in two ways. First, it is the biggest social media platform. Only Facebook rivals it.

Second, YouTube is very effective at convincing people of false stuff.

Interviews with 30 attendees revealed a pattern in the stories people told about how they came to be convinced that the Earth was not a large round rock spinning through space but a large flat disc doing much the same thing.

Of the 30, all but one said they had not considered the Earth to be flat two years ago but changed their minds after watching videos promoting conspiracy theories on YouTube.

You watch one thing, and YouTube recommends something even a little crazier and more extreme. Because YouTube wants you to spend more time on YouTube. People are calling this “rabbit hole effect.”

It’s not just happening over scientific facts, either. Many have noted that YouTube is having a similar effect in politics, with many branding it a “radicalization machine.”

Reporter Brandy Zadrozny summarizes YouTube’s defense thus:

YouTube’s CPO says the rabbit hole effect argument isn’t really fair because while sure, they do recommend more extreme content, users could choose some of the less extreme offerings in the recommendation bar.

So we need humans need to fix the problem, right? Human content moderation is the answer! Well, maybe not, because repeated exposure to misinformation makes you question your world view.

Conspiracy theories were often well received on the production floor, six moderators told me. After the Parkland shooting last year, moderators were initially horrified by the attacks. But as more conspiracy content was posted to Facebook and Instagram, some of Chloe’s colleagues began expressing doubts.

“People really started to believe these posts they were supposed to be moderating,” she says. “They were saying, ‘Oh gosh, they weren’t really there. Look at this CNN video of David Hogg — he’s too old to be in school.’ People started Googling things instead of doing their jobs and looking into conspiracy theories about them. We were like, ‘Guys, no, this is the crazy stuff we’re supposed to be moderating. What are you doing?’”

Mike Caulfield noted:

I will say this until I am blue in the face – repeated exposure to disinformation doesn’t just confirm your priors. It warps your world and gets you to adopt beliefs that initially seemed ridiculous to you.

Propaganda works. Massive disinformation campaigns work. Of course, people with a point of view and resources have known this for a long time. Dana Nucitelli noted:

(T)he American Petroleum Institute alone spent $663 million on PR and advertising over the past decade - almost 7 times more than all renewable energy trade groups combined.

Meanwhile, scientists are still hoping that just presenting facts will win the say. I mean, the comments coming from the first day of a National Academy of Sciences colloquia feel much like the same old stuff, even though the title seems to hint at the scope of the problem (“Misinformation About Science in the Public Sphere”). It feels like the old arguments about the best way that individual scientists can personally present facts, ignoring the massive machinery that most people are connected to very deeply: the social, video, and commercial websites that are using recommendation algorithms to maximize time people spent on site.

The good news is that as I was writing this, the second day seems to be much more on target. And one speaker is saying that the biggest source of news is still television. Sure, but what about all the other information people get that is not news?

The algorithm problem requires a deep reorienting of thinking. I don’t quite know what that is yet. It is true that this is a technological problem, and technological fixes may be relevant. But I think Danah Boyd is right that we can’t just change the algorithms, although I think changing algorithms is necessary. We have to change people, too, beyond a “If they only knew the facts” kind of way. Because many do know the facts, and it don’t settle matters. But changing culture is hard.

I think combating the algorithm problem might require strong political action to regulate YouTube in the way television networks in the US were (and, in other countries, still are) regulated. But the big social technology companies are spending millions in lobbying efforts in the US.

Update, 17 May 2019: A hopeful tweet on this matter.

Promising data point for YouTube’s anti-conspiracy push (on 1 topic, at least): the people in my flat-earth FB group are very mad that the site has stopped shoveling lunatic videos into their feeds.

Update, 27 June 2019:

A good illustration of this phenomenon recently appeared in a piece for MEL magazine about an increasingly disturbing trend — women whose once-promising romantic relationships implode after their boyfriends become “redpilled.” For the benefit of the blissfully uninitiated: to be “redpilled” means to internalize a set of misogynistic far-right beliefs popular with certain corners of the internet; the product of a noxious blend of junk science, conspiracy theory, and a pathological fear of social progress.

The men interviewed in the piece, once sweet and caring, started changing after going down a rabbit hole of extremist political content on YouTube and involving themselves in radical right-wing online communities. Convinced of their absolute correctness, these men became at first frustrated, then verbally abusive once they realized their female partners did not always agree with their new views.

From here.

Update, 25 August 2019: Okay, this is political information rather than scientific, but a new preprint describes how YouTube facilitates getting users into increasingly extreme political content. The dataset here is impressive: “360 channels, more than 79 million comments, more than 2 million recommendations.”

One of the authors concludes, “YouTube has to be held accountable and take action.”

Update, 31 August 2019: Pinterest gets it.

When Pinterest realized in 2018 that the search results for many health-related terms – such as “vaccines” or “cancer cure” – were polluted with non-scientific misinformation, the visual social media site took a radical step: it broke the search function for those terms. “If you’re looking for medical advice, please contact a healthcare provider,” a message on the otherwise blank page read.

On Wednesday, Pinterest announced a new step in its efforts to combat health misinformation on its platform: users will be able to search for 200 terms related to vaccines, but the results displayed will come from major public health organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), Centers for Disease Control, American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) and Vaccine Safety Net.

Update, 29 December 2019: Fascinating thread by Arvind Narayanan about this issue by on Twitter and why it.s so hard to study. Excerpt, with my emphasis added:

I spent about a year studying YouTube radicalization with several students. We dismissed simplistic research designs... by about week 2, and realized that the phenomenon results from users/the algorithm/video creators adapting to each other. ...

After tussling with these complexities, my students and I ended up with nothing publishable because we realized that there’s no good way for external researchers to quantitatively study radicalization. (Emphasis added. -ZF) I think YouTube can study it internally, but only in a very limited way. If you’re wondering how such a widely discussed problem has attracted so little scientific study before this paper, that’s exactly why. Many have tried, but chose to say nothing rather than publish meaningless results, leaving the field open for authors with lower standards. (Emphasis added. -ZF)

In our data-driven world, the claim that we don’t have a good way to study something quantitatively may sound shocking. The reality even worse — in many cases we don’t even have the vocabulary to ask meaningful quantitative questions about complex socio-technical systems. ... And I want to thank the journalists who’ve been doing the next best thing — telling the stories of people led down a rabbit hole by YouTube’s algorithm.

Update, 11 January 2021:

Facebook’s own research revealed that 64 percent of the time a person joins an extremist Facebook Group, they do so because the platform recommended it.

From “Platforms must pay for their role in the insurrection” in Wired.

External links

The trauma floor

Study blames YouTube for rise in number of Flat Earthers

Google and Facebook can’t just make fake news disappear

YouTube’s algorithms can drag you down a rabbit hole of conspiracies, researcher finds

Google, Facebook set 2018 lobbying records as tech scrutiny intensifies

Americans are smart about science

The magical thinking of guys who love logic

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)