As I mentioned last time, I'm working on a book manuscript. Why am I doing that instead of, say, writing a technical review article for a journal? There's several reasons, but it boils down to public relations.

Books get attention.

Science,

Nature,

American Scientist,

Animal Behaviour,

New Scientist are all journals that I read that have book reviews every issue. Just a few off the top of my head. Some even have occasional special book issues. There are many books that even though I've never read, I've read so many reviews about them that I have a decent idea of their arguments and what they're about.

Write a book and you might get invited to talk about it on

Quirks & Quarks or the

Science Show. Heck, the last third of

The Daily Show would not exist if it wasn't for authors plugging their books.

Likewise, relatively few people ever go in and wander around an academic library, pick up a journal with an interesting cover and skim a few abstracts. People go into bookstores and do that all the time.

Sure, the blogosphere is making an ever-increasing impact over the past few years. And there's no getting away from the importance of peer reviewed refereed journals in making or breaking scientific careers. But if the goal is to explain something about my field to those outside it -- which it is -- I think a book may be the best way to go.

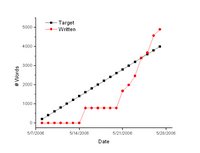

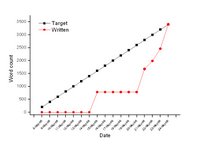

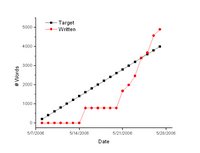

It's easy to keep up with my 200 word a day target right now (see graph). This is partly because I'm still at the point where I'm fleshing out a structure and deciding what I want to talk about. It's also partly because as I'm writing, references are going in. References add quite a few words, but don't require any talent on my part except deciding which is the right one to put in and where.

There's going to be two hard parts. One is going to come when I start hitting the limits of what I know from my general background, which will mean I'll have to find a lot of old articles to learn what I don't know. The second is going to be the point where I have the structure in place and I have enough words (or, more likely, more than enough), and have to figure how to say it all in a way that a non-researcher can not only understand, but enjoy.

;;;;;

Meanwhile, I actually had research going on in my lab this week. We finally have tunicates back, so my HHMI undergraduate student Veronica is doing some experiments with them. My graduate student Sandra got the tax return cheque that she needed to fix her rattling car, so she can now drive into the lab. Both she and I are trying to replicate some results for a manuscript that we're revising for a journal. The reviews were positive, but the referees asked us to try to refine a couple of figures.

I hope Sandra has more success than me. I set up one experiment Wendesday, and needed to finish it Thursday. I had meetings almost all that day and I wasn't able to get into the lab until quite late. And the experiment has not worked

at all. I didn't get a single datum, nothing that would help the manuscript revision get off.

The graphics on this page shows the way a webpage is written. The first one on the left is the page you're reading (prior to making this post, which should change the structure slightly). I suspect that many Blogger-driven blogs will look the same, due to common blogger templates and such.

The graphics on this page shows the way a webpage is written. The first one on the left is the page you're reading (prior to making this post, which should change the structure slightly). I suspect that many Blogger-driven blogs will look the same, due to common blogger templates and such.