On Monday, a now deleted tweet from

Andrew Timming said something along the lines of, “This crisis is a wake-up call. COVID-19 shows how much academic research is just castles in the sky. ‘Moving forward, let’s do research that actually matters to the world’.”

Andrew has

deleted the tweet, so I can’t confirm the exact wording. That last part – “research that actually matters to the world” –

is an exact quote. I don’t think Andrew deserves hate, which he says he received, but I do think his comment deserves commentary. Maybe even critical commentary.

I get the sentiment. I do. In times of crisis, a lot of people feel useless.

Timming was making a variation of an old, long-running argument about “basic verus applied” research. Now, I’ve heard a lot of retorts to this. I like, “If we only ever did applied research, all we’d have would be better mammoth traps.”

According to (probably untrue)

legend, a politician once asked Michael Faraday what good electricity was.

There are two versions of the story of Faraday’s reply.

- “One might as well as what good is a new borne baby.”

- “One day, sir, you may tax it.”

(I like the second one.)

But the next day, I was listening to Maddie Sofia interviwing Ed Yong on

ShortWave. It shows the COVID-19 pandemic

itself shows the problem of focusing research on what “actually matters in the world.” (My emphasis.)

SOFIA: So one thing that I found really interesting in your article was the state of coronavirus research in general and how that plays into how prepared we are right now. Like, this is a big group of viruses that cause a decent bit of disease throughout the world. But one researcher you talked to said that until recently, not that many people were studying coronaviruses.

YONG: Right. So a very small group of people - maybe, you know, several dozens of researchers - have focused on coronaviruses for a few decades now. But it really has been a very, very niche field, even among virologists. When SARS classic first emerged, I think coronavirus researchers were really shocked that the things that they were studying were suddenly of public health importance.

SOFIA: Right.

YONG: And they are even more flabbergasted now.

SOFIA: And so because of that - because even after SARS, there wasn’t a huge uptake in how many people were studying this, we don’t necessarily have surveillance networks in place for coronavirus like we do for the flu.

YONG: Right. A lot of our preparedness measures in general have been focused on flu as the most likely next pandemic - and for good reason - because flu actually is the most likely next pandemic. It just so happened that this time, it was a coronavirus. And we don’t have surveillance for coronaviruses. We know, actually, surprisingly little about coronavirus biology. And all of those deficiencies have contributed to this dire situation that we’re facing when we don't know enough but we're forced to act as quickly as possible.

Arguably, the situation we now find ourselves in with the COVID-19 pandemic is not

despite the view that researchers should do work “that actually matters to the world,” it’s

because of it.

From a rational assessment of risk, need, whatever, I’m sure people argued in grant agencies that we should

not invest much money and resources in coronavirus research. The best estimates were that coronaviruses didn’t pose much of a threat, so we should put that money into influenza or something else.

This isn’t even the first time we’ve seen this happen in the last decade.

Remember when people were freaking out about

zika?

(I know, it seems like something that we read about in history books

instead of only four years ago, in 2016.) The CDC director

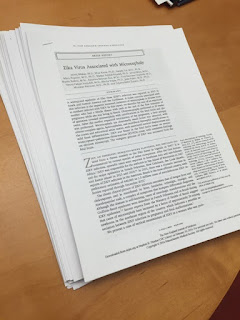

tweeted this picture of

every paper about the zika virus published

in the world to that point.

It was pretty short freakin’ stack of paper. And the

headline was that scientists were caught “flat-footed.”

I’m sure that on September 10, 2001, there would have been a lot of people in the US arguing that universities should think about shuttering programs in, say, contemporary Islamic thought or Arabic language studies.

If we discovered an comet, asteroid, or meteor on a collision course with Earth tomorrow (and given how 2020 is going, I feel like we should be watching the skies more), the headline would probably again be that scientists were caught flat-footed. Even though people have known this is a possibility for decades.

Hell, Hollywood knew this well enough to make a

movie about it in

1979. And Sean Connery disaster from space movies are the best disaster from space movies. (Don’t @ me,

Armageddon and

Deep Impact viewers.)

Things are only irrelevant until they’re not. And then people complain, “Why wasn’t anyone studying this?!” Society pretty much told us not to. Society told us that we weren’t doing research that “actually matters.”

External links

Why is the coronavirus so good at spreading?

One tweet that shows how the Zika virus caught scientists flat-footed